We publish an extract of a research report by prof. Monica E. Mincu (University of Turin) on the personalisation model developed by Cometa and the role played by tutors-educators. The integral version (in Italian) can be asked to paolo.nardi@puntocometa.org

(This research has been kindly funded by Fondazione San Zeno)

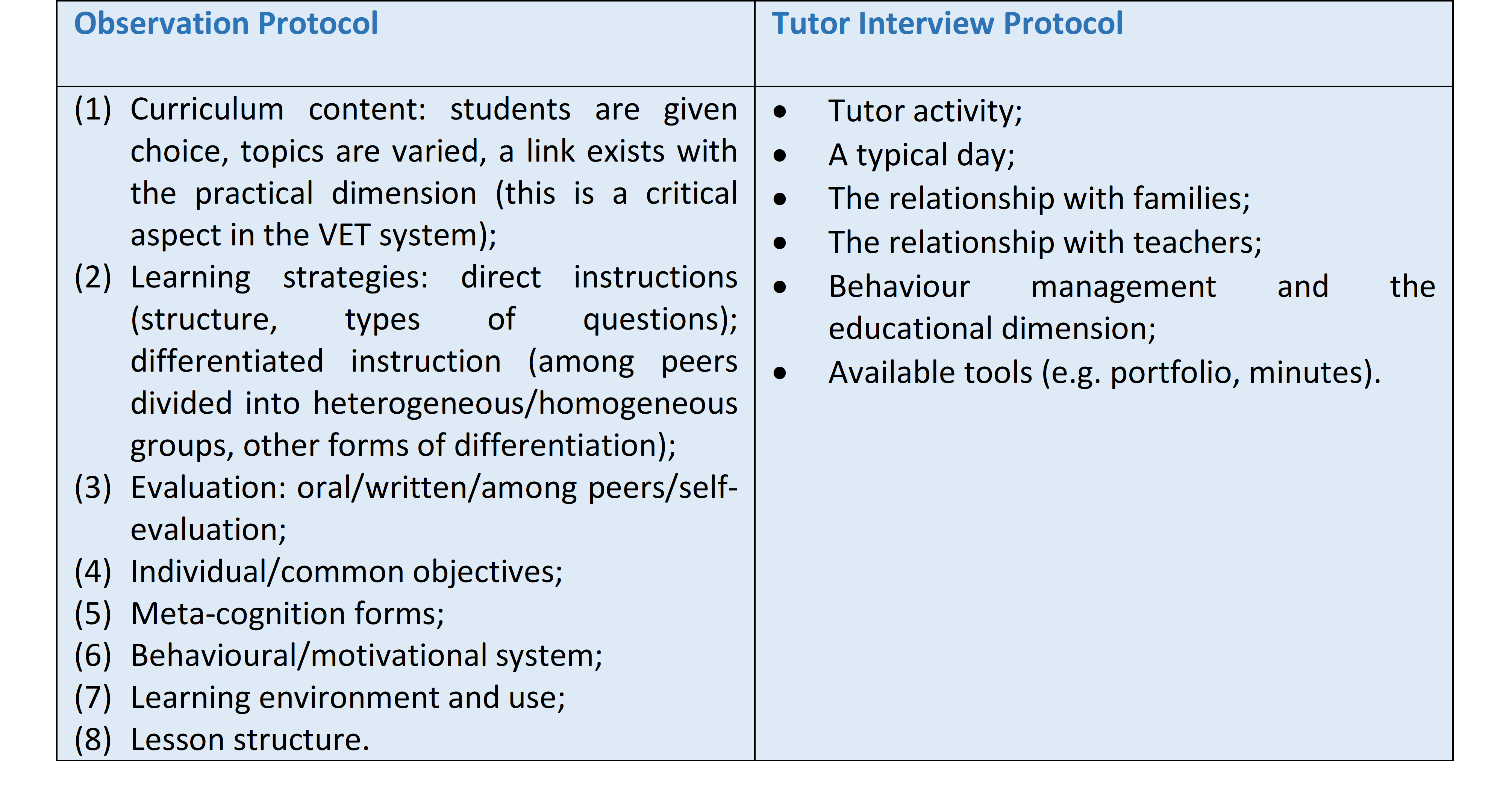

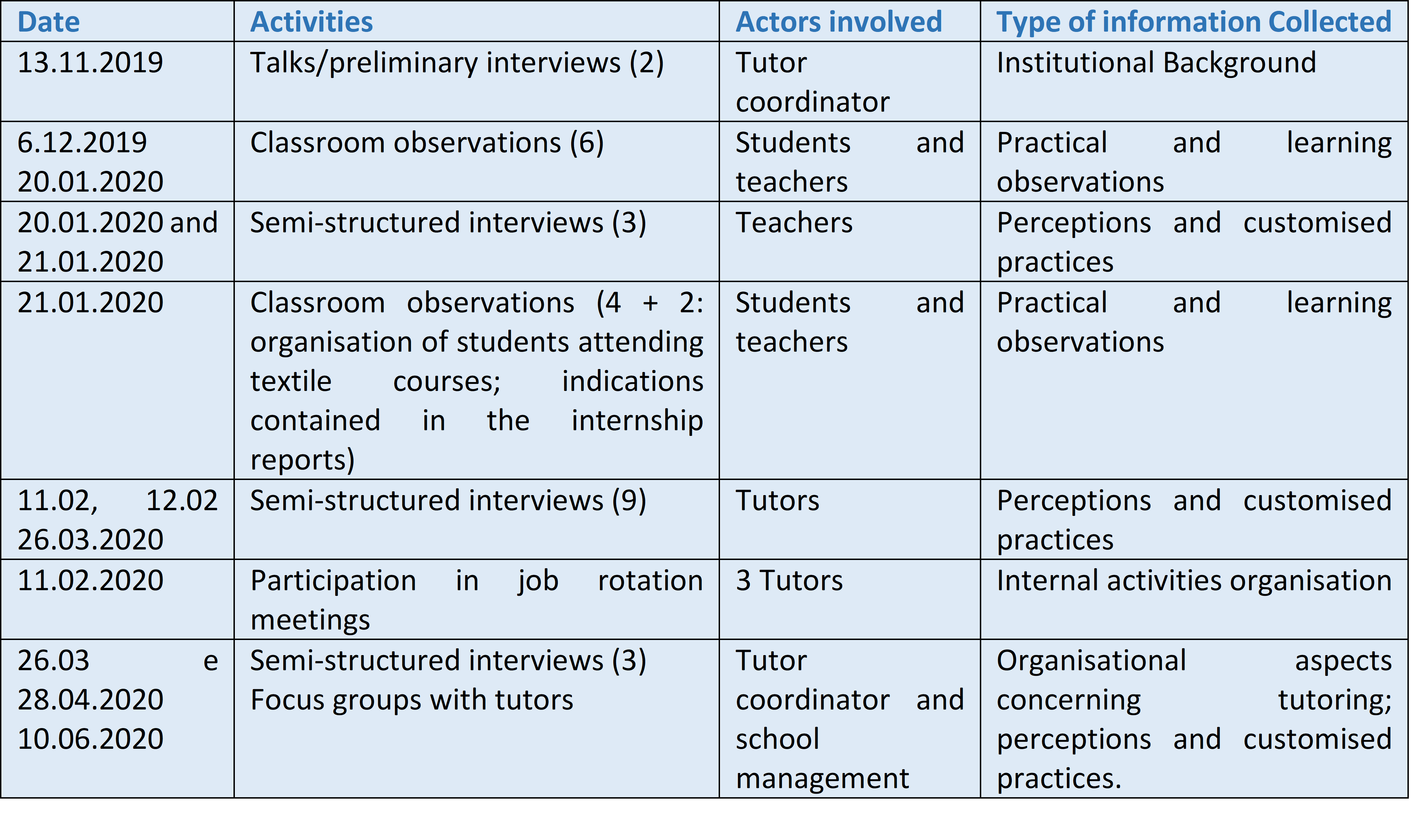

Fieldwork

Fieldwork (i.e. qualitative data collection) started at Cometa on 13 November, through two informal talks with the tutor coordinator, while in December a number of classroom observations were arranged. In January, three interviews and nine classroom observations were organised. As for the interviews, one took place among textile course participants, and the other two involved a tutor and a group of students. Nine interviews were conducted in February, while in March and April 7 semi-structured interviews were carried out remotely. A last meeting was arranged in June in the form of a focus group with some tutors and their coordinator, in order to provide feedback on the data collected. This report has also benefitted from internal research material or working tools, such as student portfolios and staff meeting minutes.

Personalisation at Cometa

It must be stated at the onset that in the Italian context and in relation to VET, ‘to personalise’ refers to the tools made available to students with special education needs (SEN). To use administration terminology, “SEN students” are those who are entitled to personalised services because of certified learning difficulties. Yet this concept has been revised recently, in an attempt to refer to an educational strategy applying to all, that is universal.

As pointed out in the document ‘Ordinamento dei percorsi di IeFP di secondo ciclo della Regione Lombardia’ (Regulation for Lombardy’s secondary VET schools), “special tests” or personalised programmes concern “students with a certified disability”. Concurrently, the regional legislation tries to make a step forward, specifying that:

Personalisation does not refer only to measures targeting individual students or groups, but it is a dimension characterising the entire learning process, a way through which all learning situations and programmes are set up (2013, p. 5).

The shift between a narrower and a wider meaning of the term can be found in the terminology employed by some teachers and tutors at Cometa. Yet Oliver Twist, which is the centre for vocational training examined here, features a universal approach, which includes many structural and systemic aspects characterising personalisation at both classroom and school level. At classroom level, some welcoming and caring approaches are in line with Oliver Twist’s underlying community dimension. The fact that the school can select its teachers and educators contributes to strengthening the school community based on shared values:

We are less formal than a public school (…) we do not give too much weight to form, we are not interested in that, because we think that form and content are overlapping concepts. We hold meetings with the teaching faculty, yet most work takes place daily while we eat, in the halls, in spontaneous routine with those who agree to participate

(G.F. the School headmaster).

Caring for less motivated students or for those who are more exposed to the risk of early school leaving takes place in a number of ways: promoting space aesthetics, providing guidance not only in relation to school but for life, more generally, ensuring tutor presence during recess or moments of socialisation. The idea of care is also implemented in a more effective way, by focusing on individual success, as explained by the school headmaster:

Life is a relationship, it disrupts all plans. That world is over and we are lucky in living

this family-like experience. When you have a son (which is a teaching paradigm) and you have not learned the multiplication tables, then you are insufficient. No, it is not enough … what do parents do? They try everything to teach multiplication tables, they turn them into a game, they do everything they could. With a son there is no plan, there is care. They love him, one truly educates oneself (G.F. the School headmaster).

The work of tutor is a veritable job. It is hard to put it into words. There are so many dimensions we deal with in our routine that it is difficult to explain… It is up to me to understand if the kid that morning does not manage to wake up, if there is a situation in the family, if I have to invite him for launch to chat, to buy him breakfast to wake him up. Work concerns both the human relationship and observation (Tutor)

School pedagogy makes use of a problem-based learning approach. This is so due to the specificity of the vocational path that consists of workshops and company internships and is intended to ensure access to work. This form of pedagogy takes place transversally and is based on a “real task” (e.g. the assignment), that is the realisation of a commissioned item as an educational and real assignment. This way of looking at things extends to more formal classroom teaching and learning, yet with some resistance, due to the wider pedagogical culture of Italy’s education system:

You have to bring kids into play, the self can be discovered in action. If you give only an explanation, you do not provide any room for personalisation, because you do not allow the kid to express, either in positive or negative terms, let’s this be clear… The core of personalisation is that action should take place in the classroom. You don’t teach history, you give them a history or maths problem (the School headmaster).

After all, it is a “culture based on pedagogical norms” (AM) which is later on implemented in class by means of indications provided to organise the lesson (with an initial moment – ‘do now’ – and a final ‘exit ticket’ which properly accompany students when engaged in their tasks, generating a proper degree of attention and interest) and with flexible learning, set up with tutors who offer their significant contribution in terms of personalisation. The way personalisation is conceived here draw on the learning environment – like the models implemented in the USA or in the UK – which Oliver Twist managed to create. The main aspects are:

– the care for the physical environment, which is highly educational, in that it provides a clear idea of individual care. Kids are impressed since their arrival at school and liken this place to a bank, a hotel, quickly understanding that carelessness would be inappropriate.

– personalisation through professional learning (learning by solving actual problems). The tutor coordinator challenges the others’ thoughts. It is always a discussion on the kid and with other teachers to challenge themselves. During the monitoring process, a kid is helped to question himself, questions are asked, opinions change, everything is reviewed together. Seeing one another in the morning is important for the success of lessons.

– The experienced eye of the tutor as an educator in relation to care. We look at classroom active participation, the homework (assigned by the teacher), the relationship between peers, the motivation to engage in this path, to participate in the internship, in work, compliance with rules, behaviour. They are all aspects that make up a person, so they will enter the labour market and will be able to deal with strain and frustration.

– Routine as a way to deal with fatigue, as is the case with routine in class, the start and the end of the activities are intended to manage transitions.

– The community with its citizenship rules, which are taught to children through two initiatives “All is for me” – which takes place weekly and all classes are involved – and “All is for me in the world”, i.e. volunteering at the Caritas soup kitchen.

– Teamwork, which involves a number of professionals – e.g. teachers and the faculty – to ensure the student finds his own balance. It is important to strike a balance between the student’s learning and personal dimensions, which often collide. Personal needs might also affect learning ones. So a way should be found to proceed with both (i.e. we are aware of teachers’ role and they are aware of ours). We try to adapt to one another in order to help the student to succeed. Sometimes one aspect is given priority over another, but the reverse is also true.

– Sanctions followed by a restart of the event. Our main approach is that we do not punish those who do not comply with rules. Along with the coordinator, we come up with many ideas to turn this punishment into an activity, e.g. engaging in the community service under the supervision of an adult. There is never a punishment in a strict sense.

– The most important component to implement personalisation is the tutor, as delineated in Cometa, which involves making use of space both outside and inside the school, trying to oversee things: lessons, workshops, informal spaces, internships, the world of work, the family context etc.

The Tutor at Cometa

Legislation at a regional level makes reference to two professionals: the teacher/educator and the tutor. Teachers/educators are in charge of: educational strategy planning and dissemination; personalised support and guidance; provision of the learning material, the tools and the equipment; management of relationships with students and their families; learning evaluation; relationships with companies and company tutors. The group of teachers/educators is the body consisting of all the resources working on the development of learning standards for a given group of students (depending on the class, the level, the interest, the tasks and so forth). Conversely, tutors are in charge of: supporting students or groups of students for whom special support is provided; supporting students, overseeing proper assessment, management and performance of the activity while at work when engaged in training or in school-work alternation paths or apprenticeships, also for the purposes of skills certification; supporting students in credit certification and access to new opportunities.

One might note that tutors in Cometa perform a wider number of tasks in relation to support concerning training, apprenticeships and school-work alternation. Together with the teachers who are tasked with teaching in class or in workshops, tutors at Cometa are more similar to teachers-educators, to use the terminology employed before, as they deal with all the assignments laid down by relevant legislation, save for learning/teaching. As indicated by Cometa’s tutor coordinator, they are engaged in the following activities:

– personalised support to students;

– definition of flexible measures and initiatives to deal with learning gaps;

– management of relationships with students and families;

– provision of learning material and equipment;

– relationships with employment agencies and local companies;

– evaluation of activities in relation to school-work alternation and apprenticeships (Sapienza, 2020).

Currently, there are 11 tutors and one tutor coordinator at Cometa, who attend to one or two classes (25 to 50 students). Area coordinators supervise tutors and, indirectly, the other classes. Every year, tutors can swap class, while they are a fixture in relation to other activities (classes concerning wooden, textile, and the bottega del gusto), because they have significant expertise which might favour technical skills development. Tutors’ activities are described as being focused on three processes: 1) the educational relationship 2) mediation between the school and the families, teachers and students 3) alternation – i.e. planning, monitoring and evaluation – which implies placements, interviews with company tutors and with students, guidance and coaching (Sapienza, 2020).

Processes and Aspects Managed by Tutors

- “A tailor-made suit for each of them, starting by lessons”: Class Tutors

Tutors play a key role and the school revolves around them, because they manage and bring together the different dimensions of the schools, placing students center-stage. Furthermore, this way of conceiving personalisation “does not simply means giving attention to teaching, because it is based precisely on a person who is assigned this task who helps teachers to coordinate one another, to get to know students and to implement teaching” (GF). As required by regional legislation, there should be a tutor in each vocational training centre. The tutor should manage school-work alternation. Yet at Oliver Twist, this function “has a mostly educational character” and is concerned with creating a tailor-made path through “activities and projects intended to promote educational success and individual excellence”, so school-work alternation is just one of the many aspects they dealt with (Cervellera, 2016).

In a narrow sense, personalisation is promoted in line with what is laid down in regional legislation. Strictly speaking and as explained by one tutor “personalisation is about a number of daily actions which do not target anyone, because some situations are fine the way they currently are”. Some tutors say they have little experience as regards personalisation planning, while others state that they focus on 5-6 personalised projects or on 5% of a class, pinpointing those measures that facilitate learning inside and outside the classroom.

We lay down a plan to help them make it until the end of the year. If a group of students needs

personalisation, we try to implement it. The personalisation I intend focuses

on the kid who risks early school leaving or has problems at home and aims to offer support during studies.

Teachers and tutors complement one another and, metaphorically speaking, they are modelled on the mother and the father figure.

The teacher and the tutor perform two different roles. The tutor must make sure that the student learns not only subjects but the whole educational proposal. It is a type of support provided to the teacher to know the students and their struggle and to help teachers work together. I think that in cross-cutting projects the tutor is a sort of “event organiser”, unlike the teacher, who is asked to keep a certain attitude with students. It is about a professional and human relationship, which at times leads to arguments and misunderstandings, which are necessary to understand each other… Dialogue implies by definition different, and sometimes conflicting, standpoints, but this takes place within a collaborative dimension, which is the final aim. They perform two completely different jobs and look at different aspects because they have different expertise (GF).

Tutors’ more specific task concerns supporting teachers with student evaluation during workshops. However, tutors enable learning in a significant way, as they put forward suggestions in relation to class organisation, ways of working which are more suitable to each student or teaching strategies. The way tutors interact with teachers can be equated to an even-moving boundary, an aspects Cometa’s leaders are fully aware of. Tutors no longer serve as silent observers in the classroom or educators who can provide a full picture of students. “Now a step backwards has been made, because at Cometa tutors used to work as class coordinators” (AM). On the one hand, it is necessary that “teachers leave their comfort zone”. On the other hand, we are aware that there exists a moving boundary between the role of the teacher and that of the tutor and that “an organisation is healthy only if is mobile, otherwise it becomes fossilised” (AM). Tutors are aware they do not have to replace teachers and that they do not have to delegitimize them, as both of them perform educational functions.

Here is a piece of advice we have given to our colleague “you don’t have to intervene regardless only because that is the teacher’s moment. The teacher does not only give class, but he is also an educator. So if he throws the chair on the ground, the tutor does not have to intervene. Never. Because what happens next is that they turn to you for things they can perfectly deal with themselves…. they get used to it and then students too no longer consider them to be an authoritative figure, which is not good. The educational function cannot be delegated to tutors completely”.

Nevertheless, in reference to basic subject matter learning and learning taking place at workshops, Cometa’s tutors play a particularly significant role. It is about promoting a behaviour that is suitable to learning and a good relationship with the class as a learning community, while implementing different learning strategies targeting more vulnerable students or groups of students. Therefore, an almost natural shift takes place from the tutor’s support to each student to his support to teaching, more generally. In effect, the teacher and the tutor cooperate on questions related to general pedagogy, learning and teaching strategies, teaching differentiation, soft-skill evaluation. Some examples of this are provided below. It is about making suggestions about teaching strategies, either spontaneously or upon teachers’ request. It is important to refer to good relationships, at times going through homework with students when indicated by the teacher, at times putting forward solutions depending on the group involved, being “supportive” with “diplomacy”.

A given lesson might not be suitable to the age of students or to the students we are dealing with. If you are under the impression that there is cooperation among teachers, you let it go. At the end of the lesson, usually in the afternoon, I feel myself lucky because I can talk freely with my colleagues: “You know, I saw that students struggle with this kind of lesson. When I am free, let’s try to propose some group work and let’s see how it goes…” Younger kids have more difficulties in managing in-person teaching… more interactive things are needed, but we talk freely.

When it comes to students’ behaviour and resilience, tutors feel this is part of their expertise:

We intervene on student behaviour, we always talk with the teacher and look for ways to get students involved – group work or ways to place them center stage – asking the teacher about the right moment to do some mini-lessons with them. Obviously, we cannot do this with all students, so we proceed through a trial and error approach.

However, it should be noted that “the trained eye”, which is an important tool for both working and engaging in the personalisation process, might lead one to deal with general pedagogy and a specific subject-matter, which should be the teacher’s responsibility. The tutor then suggests doing more interactive teaching strategies or group work, or alternative teaching solutions benefitting students:

We do not manage the cognitive aspects, but we look for ways so that all students benefit from the lesson. We are in the classroom to support, together with the other teacher, who helps those with cognitive issues. It is a sort of teamwork involving teachers and co-teaching activities.

Tutors cooperate with teachers also in relation to evaluation, as during teaching staff meetings they discuss grades or possible solutions, in consideration of individual paths. They do not claim to be “do-gooders” and do not consider teachers to be strict. Yet, it is illustrative that it is for tutors to cheer up those students who are dissatisfied with their grades or to point out when students should be praised for their performance:

We need to talk to students frequently and explain to them the evaluation they receive. While it seems like a huge effort, it is always necessary to encourage… but it is also nice to praise someone for a good grade. We cheer up students who receive bad grades, explain the reasons for them, tell them how to make up for them, the sense of the evaluation. But we forget to praise outstanding students who get 90, who always do their homework. What a bore! Always good grades…

In relation to academic provision, tutors are in charge of coordinating homework and promoting inter-disciplinarity “asking teachers to carve out some time” to develop specific projects:

The homework assigned, the timing, the content proposed, and the aggregation of topics from different disciplines. Sometimes the tutor serves as a link between colleagues… so they act on all levels, either teaching proposals or homework (GF).

Another relevant aspect is the expertise gained in terms of communication with teenagers, so tutors can suggest that teachers can use some communication strategies: “if they talk to them head-on, they might not answer”. In other cases, it is a veritable relational negotiation, a complex activity of reconstruction made of suggestions, which sometimes verges into general pedagogy:

It happens with a class… there is a kid who has problems approaching the teacher. A solution is needed because the student ditches school to avoid her. There is a need to mediate with the teacher, which among other things is old school.. a very rigid, old-style teacher. So mediation is particularly problematic in this case. I suggested engaging in research work on a given topic to break the ice, rather than give questions and make an assessment. I suggested presenting research in front of the class.

The ‘trained eye’ considers students’ attitude towards learning and those abilities that can support them beyond school, e.g. at work:

We look at the class’ active participation, the homework (assigned by the teacher), the relationship between peers, the motivation to engage in this path, to participate in the internship, in work, compliance with rules, behaviour. They are all aspects that make up a person, who will enter the labour market and will be able to deal with strain and frustration.

Finally, during teaching staff meetings, tutors put on some slides discussing aspects they think they are relevant, producing minutes. Tutors can provide teachers with information collected after internships or other activities allowing them to observe students “not only from the front, but also from behind”. Tutors can interact more formally with students participating in the internship educational units (UF stage in Italian) and they can “perform real-time monitoring” on their grade and attendance, communicating with all those concerned.

The opportunity to restore the boundary between the role of the tutor and that of the teacher in relation to classroom learning is closely related to the structural and cultural organisation of Italian education, which affects more the teachers and the tutors. It is about implementing effective strategies to be carefully adopted for groups or individual students, providing more space to the individual and more flexibility in terms of content and evaluation. One of the main issues to deal with is to review the curriculum in an innovative way, i.e. starting from actual problems that can be solved through knowledge.

The first is the bureaucratic organisation of our education system which – like in the army – thinks to give top-down instructions, an aspect which runs counter to the sense of a community. So you have to adopt a bottom-up approach, encouraging the community to make a proposal. There is a problem upstream, as we have relied on a bureaucratic system which paralysed over time. The most resilient teachers adopt a sequential approach and have difficulties rethinking the curriculum considering the activities. Resilience arises, a sort of eureka generates when they realised they can do anything, they can engage in experience through reality (AM).

The upshot is that teachers are strongly affected by the organisation and the culture of Italy’s education system and this imprinting can be seen also in a school which can select the teaching staff on its own, which offers them a community dimension and which reviews school culture in an innovative way.

The main difficulty is that teachers are used to a certain approach and nobody ever asked them to change. They always acted in the same way for which they are not accountable. Resistance to change mostly originates from teachers’ established approach, which is innate (AM).

To sum up, it is important to point out that the classroom is key to promoting personalisation (Watkins, 2012). In a similar vein, succeeding in basic subject matters is relevant to overall educational success. Consequently, care for students must consider the processes and the dynamics taking place in the classroom. Tutors’ assumption to “start from what happens in the classroom” is legitimate. “I can understand the motivation of a student by looking at how they do their homework, the relationship with their peers and with the study group. We take it from there, anything revolves around learning within the school, we cannot separate them”. However, as tutors are enablers and not decision-makers in the context of formal learning, their role overlaps with that of teachers when it comes to daily activities (general pedagogy) and education and care, more generally.

- He Takes Stock of the Situation and Decides on the Future:

The Tutor beyond the Classroom

The tutor-educator performs a number of class and extra-class activities (e.g. welcoming students in the morning, monitoring them, bringing students to the gym or to places where internships take place, sharing lunch with them, often informally to understand “how things are going”, making phone calls with parents and employers). These are tasks performed on a one-to-one basis that concern the behavioural and emotional dimension aimed at ensuring student success. It also implies organising study groups supporting individual progress, making motivational interviews, supporting behavioural management, because if “they lose their cool and get out of the classroom” they need to go after them and talk them into going back. Then there are special projects to motivate and engage them – a wall painting, the chorus – which supplement traditional daily tasks, along with meetings with students and teachers. The difficulty lies in the educational and care relationship which takes place informally, when students perform their duties, or “here and now”, to use the words of a tutor.

Who are these students? How do tutors consider them? Firstly, we need “to dispel the assumption that only misfits attend these schools, even though they are the most vulnerable ones” and even though they are remissive, passive, and struggle in relations with adult. The other consideration is that:

Today’s target group is affected by depression, social malaise, has relational issues. This is the target group one deals with, there are not serious behavioural problems. They have had a difficult past, are submissive, fragile – absences, poor resilience, poor presence.

Thus tutors must “set the basis for the desire to shine” they must “deconstruct a false image and create an educational path which sounds familiar (identity)”. Working on one’s identity through vocational training is at the same time potentially invaluable and highly complicated. It is not about managing:

One’s behaviour in order for it to be suitable. It is about finding a place in the world, developing cross-cutting skills, having care for details, acting as a mirror for the kids. Have you noticed how you replied, how you reacted? What is at stake here is the construction of a new way of living, which allows building one’s future.

Who are tutors? And do students consider them? Students understand the tutor as “a one-man band”. They are perceived as being closer to students, through an informal approach that generates closeness and trust:

Our relationship with students is more direct than the one they have with teachers. It is not a friendly relationship, but a more direct one. They respect us a lot, they learn to trust us, some of them take less time, some more. You can see this from small things, from events in everyday life. It is not about sharing personal things… this could happen in the event of serious situations… we are a reference point for them. If the laptop does not work, they call the tutor; if they cannot hand it the assignment, they call the tutor (but this is wrong). They call us, as if we were their mother. During recess or when we bring them to the gym, some informal moments are created to spend time with them, during which they share the most interesting aspects of their life.

Tutors provide one-to-one support at different levels. They provide motivational and behavioural support, assistance in relation to both working and personal life, helping students to learn technical and basic subject matters. Most work is concerned with organising personalised paths or remedial courses “during a one-to-one class, during a working hour, when there is some time available, deciding with teachers the students that need to be involved”. Support is total when the tutor works with the placement office to find a job for students, although some argue that:

They don’t know how to behave in a work environment. It is not easy when you are 17, as many are afraid of making mistakes: How can I move past a mistake? What do I do if I struggle or I want to call it even? What gives you the strength to go on? Tutors must be specific, it is not enough to say “you can make it”. They need to understand the strengths, finding an alternative solution, go into detail about what is happening and adopt an individual approach in relation to each path.

- “I Become a Carpenter by Osmosis”: Workshops, Extracurricular Training (Internships), Vocational Guidance, Support to Technical Teaching

Oliver Twist is a vocational training centre, the aim of which is to train students for a profession. The curriculum includes VET and some courses set up to tackle school dropout by school-work alternation, helping students to enter the labour market. As pointed out, there are three specialisations:

– workers in the catering sector – staff working in restaurants and bars;

– workers in the wooden sector – furniture technician;

– workers in art manufacturing – textile sector.

Starting from their second year, students engage in curricular training at companies lasting 2 months. Tutors are important in relation to curricular training planning, evaluation and provision, so their role bears relevance especially when it comes to implementing actions intended to promote student work experience.

– planning curriculum for each student and searching for a company where the internship can take place;

– identifying a tutor at the company, who can supervise the student in an effective and authoritative way;

– interviewing students about their strengths and weaknesses, their objectives during the internship, their preferences in terms of time and place; identifying shared objectives in relation to school-work alternation; meeting the placement officer at the school and matching the student with the company;

– preparing the necessary documents to start the internship: evaluation sheets concerning risk assessment at the company, the training plan and the training convention;

– engaging in the provision of school-work alternation schemes;

– providing educational support helping students to benefit from a learning experience helping them to grow as professionals and human beings, organising tours at companies on a two-weekly basis.

– meeting with the company tutor, who discusses the skills developed, the gaps to be filled, students’ possible issues and struggles;

– monitoring the necessary documentation, e.g. the training register that the company tutor and the student need to compile on a daily basis, specifying attendance, working time; providing support if issues arise;

– arranging students’ return to school after the internship, after compiling their log which will be used to write a report about the internship, which will be included in the final examination to be awarded a vocational qualification in their third year;

– providing satisfaction surveys in relation to the internship to be handed out to the company and the student; controlling and archiving students’ attendance sheet and engaging in individual meetings with students and company tutors;

– looking into the opportunity for the student to work with companes in the future;

– coordinating teachers and sharing the student’s internship experience;

– assisting students when engaging in the internship, supporting and encouraging them.

It should be stressed that tutors at school play a key role in curriculum personalisation in cooperation with teachers, to adapt training projects to current labour market needs. The attempt is to avoid that “the subjects taught in class are perceived as not relevant for students”, because “it is in their daily effort to solve problems that students revalue the desire for knowledge” (Cervellera, 2016). In vocational training, tutors act as an educator and as a support, relying on some technical skills developed in their field of expertise and based on their inclinations. The conversations with the school management point to a willingness to devote more time to workshops and support those who struggle… In this sense, tutors must be able to understand how to provide guidance. When they deal with a “development block” they must think about personalised strategies or solutions to advice students effectively. For example, a guy working in the bar is asked to work with an afternoon group in 3rd grade. Results are not satisfying, though his behaviour has improved. Tutors also manage the interviews with the company offering an internship, coordinates the monitoring process with the company tutor and assesses the internship, so they have many responsibilities. As said, overseeing means considering all components:

He is very good at carpentry, while he struggles in Italian studies, and another teacher has brought to our attention some behavioural issues… Tutors decide the future for him. Therefore, the most important aspect of personalisation concerns what the student has to do in relation to work. The student expresses some wishes, tutors talk to companies, they organised a meeting and then they hire him. It is about negotiating students’ future job. This is personalisation for us.

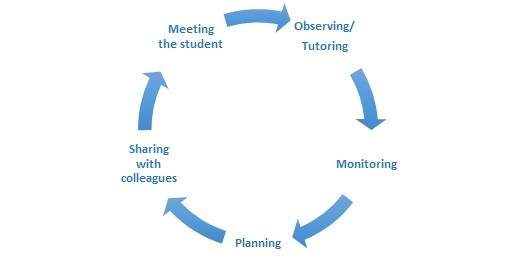

The cycle followed by tutors, which features elements of “disruption and openness” is highly personalised and is described as follows: I supervise students in all their activities (support, observation, monitoring, workshops, company, school), I share what I have observed with colleagues and then I talk to the students:

The ‘care’ relationship takes place through a close dialogue with families. There is regular contact with them and this is a major aspect of the ‘educational path’ between the school and the family. Tutors talk with families on a weekly, sometimes daily basis, with families which can ask for assistance for any kind of need, from 7 in the morning to late night: “he can’t do his homework, he does not understand maths, so we organise some remedial courses to help him understand what is missing, how to comply with rules”. Fieldwork indicates that some difficulty arises in establishing tutors’ room for manoeuvre – both metaphorically and in practical terms – especially when it comes to relationships with families, which is subject to unforeseeable events which need to be solved. Yet one tutor has stressed that “we cannot take the place of some figures, we are school educators”. We have also learned that “the family is not always a resource to tackle early school leaving. They could be anxious… They feel they have abandoned students, or their cause a failure voluntarily, they generate a crisis, or sometimes the family is completely absent”. For these reasons, it is apparently for tutors to establish an educational path, to work and support path effectiveness, in terms of attendance, material provision, clothing: “so experience teaches that if the family is not a resource, the focus turns to the kid, without excluding the family”.

Tutors’ Tools. First of all, they have hot knowledge and attitudes, pedagogical and relational sensitivity. Many tutors have solid pedagogical and psychological education and are highly motivated to perform this job.

Let’s say that, working as a tutor in a school, I rely more on pedagogical knowledge, I focus on it. I come up with some insights concerning students’ behaviour that I do not share, because at school there is the counselling service providing psychological support. You think about it, we are asked to engage in planning and more operational and school activities, but I consider all aspects beyond school, sharing them with the school’s psychologist.

For another educator, the main instrument is:

Listening, learning to listen to others, listening to others and answering on that moment. The entire skills evaluation process, helping others to identifying the skills they have developed. This is a task I am particularly interested in, I think I am not prepared at all for this, I haven’t been trained for this activity.

Another tutor classifies his tools as follows: (1) teaching activity personalisation to fill the gap (2) vocational training personalisation and (3) minutes of the meetings between tutors and parents, which are veritable technical documentation because they help track all stages, making “a weird phone call” official. There are other monitoring tools, like the template used to write the report after the internship, as in dual training – where 50% of time is spent at the company – a simple template, compiled on a weekly basis, allows focusing on each student. At the end of the year, tutors compile a portfolio, including year-round meeting minutes, so that only one file is shared with the tutor’s team. Tutors insist that the real tools are those resulting from spontaneous actions, such as class observations and talks with students having different degrees of formality. The care relationship also benefits from tutors’ welcome in the classroom:

I personally like when I ask students to hand in their cell phones. I meet all of them, they make a line and give me their mobile. You have a moment with them, a look, a joke on their jersey, the girl with or without make up. They feel they are considered, they feel it is a good day.

What they need the most is actual support, tailor-made planning, to help them achieve success:

I am thinking of some special cases. There was this kid who had difficulties staying in the classroom. I decided to personalise teaching in the subjects he struggled the most with. Studying the same subject outside class. Then he was offered the opportunity to engage in a personalised project in a company, where he could become familiar with the work environment. It was useful up to a point, because this kid had many social and family issues. We managed to help him to graduate and to finish the school year. Should he had remained in the classroom, he would have struggled.

Hot knowledge is also apparent in the advice related to general pedagogy, when they are used to support workgroups “which should be provided considering their level, otherwise you lose them along the way. As failure is related to emotional factors, to anxiety, it is necessary to”:

Plan lessons to be intended as an occasion for everyone. We must use different materials depending on the level, built paths and skills through peer education, for example the identification of topics and ways to involve all, which is an ongoing process and requires knowing individualities.

The tools described above and the aspects detailed in the report need stressing. The report contains absences, student progress, and actions implemented, and is produced once a week for each sector. It is a privileged tool because anything is tracked, i.e. all the things occurred concerning individuals or groups. The time allocated to write the report is two hours, which is not enough to examine all students carefully. Four hours might be needed, but only for some cases. Yet not only issues are pointed out, but also ‘good things’, for example those who voluntarily decided to stay at school in the afternoon. While there is an obligation to submit reports, they are now more useful and functional, in order to better help tutors. Some tutors provide personal reports when engaged in observation and they are fully aware that the risk might arise to provide an evaluation that brooks no argument:

I learned to write reports: how students deal with others, relationships at work, strengths etc. I use it this way, because I don’t want to miss a thing about what happens, I ask for feedback because sometimes it is easy to form an idea of the kid, which you impose. It is important to connect the dots, trying to be objective, to be detached.

Reports ensure behavioural monitoring, students’ attitude toward learning and the social context, helping one to identify learning problems or issues related to students’ wellbeing. Absences, progress and actions against the students are listed in special sections. After outlining the group of students, the classroom dynamic and climate, the report goes on providing an examination of those students who might face problems. Some reports provide information about a number of educational, teaching, personal, family, organisational aspects, along with elements concerning individual wellbeing attesting to students’ effective monitoring.

For example, some students have difficulties with in-person teaching while others struggle with remedial hours with teachers. Sometimes parents have doubts about out-of-class personalisation. Instead, teachers and tutors’ after-school support is consolidated and constitutes the main instrument to help students to fill the skills gap in a personalised way. Tutors always highlight issues generated by social networks and bullying and look for solutions to restore a positive environment.

Tutors regularly liaise with families to understand students’ personal and family problems. Some emotional issues are identified: frustration after being scolded, passive approach and pessimism, anxiety and stress, so students are encouraged to visit the counselling service providing psychological support, to give them some space and to return home. Tutors can ask teachers of basic subject matters to work to help students do homework or study at school, in order to establish a relationship or to develop a study method. Sometimes, in order to break from the routine, students are given personalised homework, which consists in individual research tasks. In the event of serious disengagement, tutors stay at school to make sure that the remedial activities agreed upon with teachers are carried out. Community service is used when students are disrespectful. Learning difficulties are regularly pointed out, as is the bore felt by students who could be involved in higher-level activities. Tutors can also report to teacher the need to give students extra material or to study with some peers who might have problems. Here it should be stressed that differentiation is not related to additional material quantity – which might discourage students – but to the quality and diversity of the assignment (see the possible types of differentiation).

The report produced by the area coordinators having educational responsibilities is a further tool through which higher-level organisational solutions and problems are identified. Questions concerning teacher staff meeting are discussed, as are learning and educational issues, the role of workshops as ways to engage in inter-disciplinary activities to bring together the “professional and the learning” dimension, some proposals concerning lighter working time and forms of job rotation, the type of guidance provided, open day arrangements, and other cross-cutting issues.

One relevant aspect is student assessment, both in relation to their work (criterion identification), and subject-matter teaching, so reflections are made on the possibility to grade homework, on the need to better explain success criteria and to do homework. Evaluation clarity is a central aspect for student wellbeing and classroom climate, as much frustration generates out of grading. Another issue which is widely discussed is to provide an evaluation of student behaviour which should be different from that given for cognitive progress. The risk that teachers can use grading as a form of punishment is acknowledged, along with the possibility that teachers and tutors might be seen as epitomising two different dimensions: teaching vs. education, teaching rigour vs. care and relationship. The need also arises to provide a pedagogical alignment (“we need to go together”) while having different roles also by school guidelines, which originate from the bottom up and in a collaborative way.

The portfolio is an additional tool that tutors can use and that collect observations, information about the internship, the summary of annual progress and future projects. Along with the development of soft skills at the beginning and the end of the educational path, work experience is also assessed. The example provided below signals strengths and weaknesses:

The company regards the student’s professional skills as appropriate. As for soft skills, some of them are poorly developed, e.g. interaction with supervisors or with colleagues (insufficient skills) or the ability to adapt to the work environment. Sometimes, low collaboration and availability have been reported, with little motivation. Some positive aspects of the students relate to the fact that he has performed the tasks assigned timely and properly.

The portfolio also gives an assessment about future planning or new guidance:

The student has attended the third year with higher motivation and the desire to succeed. Despite fluctuating attendance, the student had developed a great awareness of his tasks and sometimes has managed to seek support from tutors. Resilience and commitment are critical, while interest is highly selective.

What emerges from this tool is the rather complex role of tutors, who identify and support soft-skill development for both professional and personal life, through encouraging and re-motivating, which translate into many formal and informal actions, based on excellent knowledge of the student, thanks to dialogue with the student himself, the family and the other educational figures. The great openness of Cometa’s tutors should be pointed out. They can support students at every stage of their growth, providing them with emotional support and help to access the labour market, by even helping students who admit not being able to shave. Support in terms of soft skills is promoted through psychological, pedagogical and human skills and by helping them not feeling tired. The tutoring method has been formalised through 4 stages: observation, supervision, planning and assessment.

| Methodology | |||||

| Teamwork | Weekly Meetings | Observation | – Student observation in the classroom and during free time.

– Meetings (with): students, families, high school, social services. – Teamwork and meeting minutes. |

Daily Interaction | Teamwork |

| Supervision | – Case study Presentation (one or more students) taking place every two weeks.

– Standard templates for drawing up a report; questions and proposed planning. |

||||

| Planning | – Sharing with teaching staff.

– Coordination or management of personalized or individualized projects, including workshops and internships. |

||||

| Assessment | Project assessment and re-planning starting from observation. | ||||

Collected Data Analysis: the tutor, dialogue with similar professional and advice

Tutors are focused on students and their comprehensive learning so they are the main personalisation tools. They play a part both in relation to the school curriculum and to employment. In this sense, they are mostly concerned with serving as enablers or mediators between students and learning spheres (the academic, professional and working one) o between students and other teaching reference figures at school, in workshops and at the company. The final objective is students’ educational success and access to work. Furthermore, tutors make up a close and well-equipped group that is able to deal with all aspects, thanks to consolidated expertise developed over the years and the tutor coordinator’s leadership. The three-stage strategy aimed at building “a shared culture and a shared view on students and ourselves” develops as follows:

In the first year, we built the team helping us to become a team; in the second year, we developed adulthood, we worked on ourselves, not on students; this year, we will focus on case studies, on a common language, on the development of good practices. We always place students center stage. No difference exists with teachers as regards the perspective, while differences exist related to actions.

Concurrently, much attention is devoted to developing a shared culture with teachers, through initiatives like “the July summer camp”, which is dedicated to lifelong learning. Tutors are seen as a stimulus “helping over time and developing a pedagogical culture among teachers, turning the school into a community”. As seen, tutors have considerable skills in pedagogy and personalised learning. They are well trained to make teaching effective, as there is an actual interest in learning. In other words, what holds true for those who struggle, also temporarily, holds true for all. Newly-hired teachers who are not familiar with this approach might find it stimulating, especially because they have to see to the assignment and real-life problems, which require adopting an educational perspective. Change lies in the integration of all those concerned, which is far from obvious in Italian schools: “some time ago we used to toss them out of the classroom. Now we keep them in, we create activities at different levels”.

Tutors are fully aware of the issues concerning teaching methods and of the opportunities provided by classroom teaching especially when it comes to communication, the need to generate a common culture regarding homework assignment and so forth. Assessment is another aspect examined by tutors and with which they deal in terms of motivation in case of disappointment, discouragement or misunderstanding about grading which might not reflect student commitment or real potential. Unsurprisingly, developing an evaluation culture takes time and is a process to which everybody contributes, including tutors.

Evaluation is a major issue. This year we managed to establish a rule: you cannot give students bad grades if they do not submit their homework. This aspect concerns behaviour, as you cannot evaluate their homework. We are still defining what evaluation is, we are far behind.

One question that was asked during fieldwork and which attests to tutors’ passion and commitment has been: “What does the sentence ‘caring for’ mean in education and teaching?”. It is important to draw a distinction between the two dimensions, as the answer to this question will depend upon the perspective adopted. If teaching is not different from education – most activities concern both dimensions – then caring for people and their motivation, supporting their self-confidence and personal identity should characterise both worlds. Thus, the answer has to be found in teaching and education personalisation strategies, which might support students’ learning commitment in a proper way, i.e. by caring for them. The boundaries between commitment and learning are blurred, as no distinction is made between in-school and out-of-school settings. By the same token, the adolescent is a single individual and the contexts in which they manifest must ensure continuity in terms of vision and ways of acting. Tutors’ perception of the need of ensuring this continuity in their work can be explained through a metaphor:

We are like spiders that build webs connecting different points. Kids are the core of everything. Our goal is that all dimensions connected to kids are connected, e.g. the company, the family, social services, the educator. If parents do not talk to each other, we have to make sure that the kids are aware of this connection, which is far from complete. We are like a cane, if they want to use us. Sometimes we tell them “come on, let’s go” but always respecting their freedom.

Tutors are critical of the system and their foundations, e.g. the distinction between education and work, as if one was easier than the other, according to an established hierarchy. Indeed, “a contradiction arises. Because of maladaptive behaviour at school, a kid is better off at work”. What needs stressing here is the struggle to “find some middle ground” in a highly polarised context which considers a wider epistemological, cultural and institutional dimension. At Cometa, and in keeping with the Italian context, learning and classroom personalisation is implemented in both a marked and nuanced way. Cometa as a whole should be credited for this, together with its leaders, teachers, and tutors, who promote this culture inside and outside the classroom.

| Learning Personalisation

(marked implementation) |

Learning Personalisation

(nuanced implementation) |

| 1) Students should make a choice as regards work content and modes on an off-and-on basis;

2) Teaching differentiation practices should be implemented in terms of times, material, homework, ways of working. 3) Students’ interests and experiences should be promoted as a way to encourage meaningful learning. 4) Students’ meta-cognitive abilities should be stimulated. |

1) Creating working groups between peers, or between students having the same level or interests;

2) Engaging in regular evaluation 3) Engaging in interactive, collaborative classroom teaching. 4) Promoting teaching strategy differentiation 5) Attention to the relational dimension |

Besides being one of the main architects of personalisation and in addition to epitomising the figure of the tutor-educator as understood at Cometa, the educator also engages in tutoring, performing three roles that in other contexts are assigned to three different people, viz. teaching assistant, vocational and educational guidance counsellor and pastoral carer. In France, vocational and educational guidance counsellors are established professionals, though decreasing in numbers, tasked with providing support in relation to the academic and professional career. A national team of educational psychologists is now supporting them, as they specialise in “education, development and learning” for elementary school and in “education, development and vocational and educational guidance” for secondary school. These counsellors have been asked to ensure students’ motivation and wellbeing, to support students with special educational needs, to set up personalised educational paths and vocational guidance programmes and to tackle early school leaving. They conduct interviews, engage in observation and liaise with families, drawing up individual and group programmes. In schools and communities where personalisation is widely implemented, teachers under the supervision of the teacher coordinator carry out personal care. They have direct contact with families, help students do their homework and look after them during recess. They also monitor school climate and organise one-to-one meetings with students, either inside or outside the classroom, during remedial courses or in the afternoon, informally (e.g. during breakfast) or early in the morning to take stock of the situation. In schools where personalisation is implemented in a marked fashion, the educational dimension is linked to the teaching one in routine (differentiated) learning and is reflected in the evaluation criteria preferred by students, e.g. assessment for learning, feedback, motivational assessment, homework assigned, personal goals, ways to promote individual support, identity and wellbeing, along with educational attainment. Individual progress and objectives change radically when skills certification is in place and is carried out on a regular and ongoing basis, without grading (e.g. a letter or a number). At the end of the programme or during the year, students can have their personal objectives adjusted or are given feedback in relation to their commitment. Their progress is assessed on an ongoing basis, while at times a general evaluation criterion is applied to all.

In the UK context, teaching assistants operate in the classroom and support students or group of students who struggle. Nevertheless, their direct impact has been assessed negatively in relation to the cognitive process, for a number of reasons (Webster, Blatchford &Russell, 2013): 1) over time, they make use of the time in which the teacher specialised in the subject matter discussed provide more insightful explanations. 2) In the UK context, they are less qualified than teachers and they are not expert of the subject matter. 3) frequently, they do not have the time to discuss with teachers about how to be involved and to provide feedback at the end of the class. Their way to interact with the teacher is superficial and often ineffective. 4) they tend to focus student attention on “finishing their assignment”. 5) the way the interact with students hampers dialogue rather than encouraging it.

If the issues illustrated above are dealt with, i.e. more cooperation between teaching assistants and the lead teacher before and after class, more training on interaction strategies, the acknowledgment that teaching assistants’ activities supplement without being in contrast to teachers’, the direct impact is much more positive also in cognitive terms. As for the indirect impact (i.e. student behaviour), it is highly positive, as it enables the involvement of students in the one-to-one interaction with them. Furthermore, the role of teaching assistants is decisive to helping students developing soft skills, e.g. motivation and the learning attitude. Research points out that the pedagogical dimension of teaching, interaction and assistance targeting students must emerge clearly and supported properly. It is necessary to carve out some time for preparation and reduce reliance on assistants’ volunteering, the time of whom should be devoted to other activities. Cometa’s tutor-educator fully overlaps with teaching assistants. Unlike Anglo-Saxon countries, these professionals in Italy perform a higher number of tasks. Indeed, tutors are able to grasp some aspects related to class behaviour and climate, support workshops and the teaching of basic subject matters through their special skills or by giving advice (about general and differentiated pedagogy), supporting strategy effectiveness on the class. Furthermore, they have a particular predisposition to support motivation and re-motivate, to set up individualized projects, to mediate/negotiate difficult situation between students, teachers, and company tutors, putting forward suggestions in relation to communication practices, evaluation strategies, curriculum or assignments.

It should be added that in Italy some overlapping might exist also with support teachers, who assist the class or single students and work for everybody’s inclusion. The last paragraph of Article 13 of Law no. 104/92 specifies that “support teachers are jointly responsible of the sections and the classes they operate in, participate in educational and teaching planning and in the evaluation process carried out by the interclass boards and in staff meetings” also as members of the staff of a given school or a grouping of school.

Support teachers might be co-holder of the chair along with the lead teacher. They are assigned to a class (not to a student), as additional resources providing special teaching ensuring the inclusion of students with a disability. Together with the lead teacher, support teachers adapt teaching planning to the needs of students with a disability. In class roles might swap. The lead teacher might work with students with disabilities, while support teachers might give a lesson to the class, as they are also awarded teaching habilitation in a given disciplinary. Alternatively, the class can be divided into two or more groups, with both teachers who are assigned some of them. During the teacher staff meeting, support teacher can have a say as regards all students’ progress and behaviour. These practices favour actual inclusion. Support teachers provide their contribution in terms of active pedagogy, in cooperation with the lead teacher. From the present report, some suggestions arise in relation to tutors-educators and to personalisation strategies. The first is concerned with their multifaceted character and with the need to better define their role. A further observation concerns that teachers of basic subjects should better integrate the educational and teaching dimension, by also cooperating with other teaching staff. The third aspect refers to personalisation, as increased differentiation is recommended, especially when it comes to basic subjects, concurrently promoting an evaluation culture which must promote motivation. One possibility could be providing tutors and their “educational expertise” with specific working tools in basic subjects (e.g. monitoring strategies related to individual projects, based on realistic objectives and differentiation practices, motivational feedback promoting further learning, with grading to be used carefully).

Finally, the positive climate in behavioural and emotional terms characterising Oliver Twist can be further consolidated through a bottom-up, reward system, which can benefit from the contribution of both students and tutors, promoting everybody’s progress. Sharing pedagogical knowledge and tutors’ insights when working with other staff can help to further personalised classroom teaching.

Comparison reveals that tutors-educators are similar to UK teaching assistants – particularly when contrasting their commitment in class – and to French guidance counsellors – as far as the psychological component is concerned. Cometa’s tutors-educators perform different roles based on pedagogical knowledge and promoting learning support and care, by making use of all the opportunities made available at this vocational training centre. The centre’s prestige and students’ professional success draw on the variety of tasks and the practical knowledge of these tutors.

References

– Banzi, G. (2018) L’Approccio Educativo di Cometa. Un Rapporto sulla Scuola Oliver Twist.

– Calvani, A. & TRinchero, R. (2019). Dieci falsi miti e dieci regole per insegnare bene. Roma: Carocci.

– Cervellera. E. (2016) Il tutoraggio nel tirocinio, chiave del successo formativo nel modello Cometa https://cometaresearch.org/educationvet-it-2/il-tutoraggio-nel-tirocinio-chiave-del-successo-formativo-nel-modello-cometa/?lang=it.

– Fullan, M. (2012). Breakthrough: deepening pedagogical improvement. In M. Mincu (Ed). Personalisation of Education in Context. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

– Hart, R. (2010). Classroom behavior management: educational psychologists’ view on effective practice. Educational and Behavioural Difficulties, 15(4), 353-371.

– Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? Paper presented at the Australian Council for Educational Research. Available at: http://www.educationalleaders.govt.nz/Pedagogy-and-assessment/Building-effective-learning-environments/Teachers-Make-a-Difference-What-is-the-Research-Evidence.

– Mele, A. & Nardi, P. – L’integrazione scuola-lavoro e il modello reality-based di Cometa Formazione

Sapienza, A. (2020) Il tutoraggio in Cometa. Cometa: Materiale (unpublished).

– Mincu, M. (2020) Personalizzare in classe: la ricerca del miglioramento scolastico nel contesto italiano.Nuova Secondaria, 6, 18-22.

– Mincu, M. (forthcoming). Sistemi scolastici nel mondo globale. Educazione comparata e politiche educative. Milano: Mondadori.

– Mincu, M. (Ed.) (2012). Personalising education: Theories, politics and cultural contexts. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

– Mincu, M. (Ed.) (2011) A ciascuno la sua scuola. Teorie, politiche e contesti della personalizzazione. Torino: SEI.

– Ministère de l’éducation nationale Être psychologue de l’Éducation nationale (PsyEN) Available at https://www.education.gouv.fr/etre-psychologue-de-l-education-nationale-psyen-11831.

– Regione Lombardia (2014) Ordinamento dei percorsi di iefp di secondo ciclo della regione lombardia indicazioni regionali per l’offerta formativa Appendix “A” decreto n. 12550 del 10/12/2013 http://www.provincia.va.it/ProxyVFS.axd/null/r62675/DDUO_12550_2013_All_A_Indic_reg-pdf?ext=.pdf

– Tomlinson, C.A. (2005). Grading and differentiation: paradox or good practice? Theory Into Practice, 44(3), 262-269.

– Watkins, C. (2012). Personalisation and the classroom context. In M. Mincu (Ed). Personalisation of education in contexts. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

– Webster, R., Blatchford, P.& Russell, A. (2013) Challenging and changing how schools use teaching assistants: findings from the Effective Deployment of Teaching Assistants project. School Leadership & Management, 33(1), 78-96.