Based on empirical findings in an Erasmus+ KA2 project titled “Leadership for Learning in VET”, the purpose of this paper is to reveal an empirically based DNA-model symbolizing the individual capacity of leadership for learning. Using the term “leadership for learning”, we address the connection between principals’ leadership for learning and teachers’ leadership for learning in VET. We found the DNA-model to be built by two strands of brick-stones: “Professional Skills and Knowledge” in wired with “Personal Attitude and Beliefs”. The findings presented in this paper are the result of a multiple case study conducted in collaboration with “leaders for learning” across domains of leadership for learning, across four VET schools, and across countries in the EU.

Introduction

Previously, the leadership discourse in VET has been influenced by management theories from non-educational fields within the thinking of new public management (Cedefop 2011). Currently, the European VET governance has been influenced by policy affected by the results of effective school research, shifting management ideology toward at student, and learning centered leadership. Researchers within the field of effective school research argue that the more educational leaders focus on teaching and learning, the greater impact they have on students’ learning. (Hallinger & Heck, 2006) (Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008).

However, the agenda of this paper (as well as the project behind it) is not to examine or confirm the impact of educational leadership on students’ learning. We do acknowledge the coherence, but we do not necessarily believe in a causality or linear logic between leadership and students’ learning.

The hypothesis advanced in this project

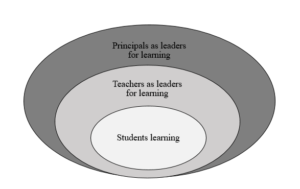

The basic hypothesis carried out in this project is the believed coherency that the way principals frame, form, and facilitate teachers’ learning is linked to the way teachers frame, form, and facilitate students’ learning. By extending this hypothesis, we assume that the relationship between the two domains and the capacity of leadership for learning practices in both will enhance the impact on students’ learning.

Figure 1: The relationship between “Leadership for Learning” and students learning

The methodology and design of this project

Purpose and focus

The overall purpose of the mentioned KA2 project is the “exchange of practices” meeting the ambition to create transnational awareness and to stimulate debate and reflection on leadership for learning. The goal of the project is to make a single contribution to the professional development of leadership for learning in VET (ref. project application).

Using four VET schools as examples, we posed the following question: Is there a uniform linking of principals’ leadership for learning and teachers’ leadership for learning? – If so, what makes the brick-stones of individual capacity of leadership for learning?

A multiple case study methodology

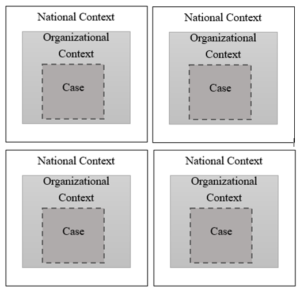

The examination of the above question is conducted by a multiple case study methodology. Our aim was to investigate the phenomenon “leadership for learning” within its “real-life” context (Yin, 2009). The transnational participation made it possible to examine four different cases – in four different countries at four different VET schools. Each school illustrated and enlightened how they practice leadership for learning. The project team then collected evidence using a mix of qualitative data. The team made observations and interviewed a variety of stakeholders, principals, teachers, and students. This way, the contribution of the case-method resulted in four various representations of practitioners (principals and teachers) engaged in real life leadership for learning.

Of course, every case is embedded in contextual conditions. As recognized, the dotted lines in the matrix below (figure 2) show that the boundary between the case and the context is not clear-cut (Yin, 2009).

Examining leadership for learning across national and organizational contexts, we acknowledge the influence of the specific context of the school and the relevance of the national culture. These cultural hallmarks (Stringer, 2013) have been an important part of the discussions during the project. Nevertheless, a crucial part of this project’s inquiry is to look beyond the contextual preconditions and look for more generic capacities in “leadership for learning”.

Figure 2: A Multiple case design

Collaboration and knowledge-building

The heart of this project design is an inductive process of ”knowledge –building”. We consider the process both systematic, pragmatic, and collaborative. When analyzing the local data set, the project team asked each other the following:

A: What did we see? What did we hear?

B: What is worth analyzing, and what do we think?

Every word and contribution from the participants were written on a blackboard for everyone to see and for everyone to look for meaningful patterns to emerge. This process of mapping was repeated in the same way in each case. Finally, the team worked across the four cases looking for contraries and matching patterns revealing the brick-stones linking principals’ leadership for learning and teachers’ leadership for learning.

Limitations

It should be noticed that the findings of this project are the result of practitioners’ collaborative study of their own practices. The results are purely based on empirical studies, and the prediction is limited by the relatively small amount of empirical data (four local cases). Therefore, the results require further clarification and theoretical validation. For a theoretical validation, the findings may be compared to the research field of capacity building of school improvement (Stringer, 2013) (Timperley, 2011) (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2017 / 2012).

Building a collaborative and transnational network of leaders for learning

An important validation of the knowledge building process is the quality of the project team as professional peers. The project is designed for educators to look at the work performed by international colleagues. This method may give rise to “finger pointing” or “back-scratching”. However, this was not the case and the project team had full benefits of collaboration. The continuity of participation and methods ensured commitment and promoted reflecting conversations in an environment of critical openness and respect of the professionalism of all the participants.

The importance of a school vision

Despite the focus on the individual capacity, this study revealed the importance of a “school vision”. Across cases, the vision for the school varied in content and assumptions of the greater goal. However, the visions reflected an overall concept of what the educators wanted the organization to stand for; what its primary mission is; what its core values are, and how all parts work together (Barth, 1990). In each case, a clear and meaningful vison seemed to represent a driving force and cornerstones for building and carrying out individual capacity for “leadership for learning”.

A DNA-model of individual capacity of “Leadership for Learning”

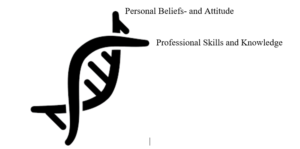

At first, the findings of this case study pointed out a substantial connection between principals and teachers’ capacity of leadership for learning. We found two sets of personal attributions building and carrying out individual capacity for leadership for learning:

- Professional Skills and Knowledge

- Personal Beliefs and Attitude

It is important to notice that we found the two sets of brick-stones to be interdependent or synergistically integrated. Inspired by the drawing of two DNA strands intertwined around each other forming a double helix, we worked within the symbolism of a DNA for “Leadership for Learning”.

Biological DNA contains the components needed for an organism to develop, and the DNA strands of “Leadership for Learning” consist of the brick-stones needed for building individual capacity for leadership for learning. Each of the two strands contain a line of brick-stones or practical codes inherent in leadership for learning.

Figure 3: The DNA-model with strands of “Professional skills and Knowledge” and “Personal Beliefs and Attitude”

Working and thinking “student centered”

Looking for brick-stones, we found that the overall mindset framing the DNA of “leadership for learning” is working and thinking “student centered” (Robinson V. , 2014). Placing students’ learning in the heart of leadership for learning implies that every consideration that does not in some way improve or facilitate students’ learning would become secondary in importance – for example regarding teacher education and collaboration.

The brick-stones of professional skills and knowledge in “Leadership for Learning”.

Findings across all cases revealed a line of brick-stones building a DNA strand labeled “Professional Skills and Knowledge”:

- Communicating and living the vision:

Communicating and living the school vision is to enhance the organization towards visions stands. It is about giving meaning to the work that teachers and students do in the school. We found that to lead learning, it implies generating shared values and norms about learning which ensured a consistency of action.

- Collaboration (working and framing)

Collaboration means more than simply working together. Collaboration implies a shared goal or activity that we agree to pursue together. In this context, we found educators engaged in mutual dialogues, supporting and empowering each other to improve practice while recognizing that agreement on educational values and having a shared language about the process of learning made an important attribution.

- Doing inquiry based development

While doing inquiry-based development, you continually try to make things better by evaluating the impact of your own and others’ practices. We found that leading learning entails collecting and analyzing data when it serves the stakeholders’ need to know and improves their impact on students learning. Inquiry-based development is a scaffolder and systematic process of practice study and knowledge building, and it makes an on-going part of professional development.

- Monitoring quality

Monitoring the quality of learning practices is not to be confused with doing quality control. Monitoring quality is based on reliable and authentic information (data) in use for formative evaluations – not summative. The aim is to promote individual and organizational learning. As examples, we found teachers and principals working with students’ feedback, peer-review, classroom observations, and assessment systems to monitor the quality.

- Directional/Normative

By using the term directional or normative, we assert the finding that the capacity of leadership for learning implies working with the setting of clear expectations – also indicating that some actions or outcomes are considered more desirable than others are.

- Establishing an open learning environment

An important part of leadership for learning is the ability to facilitate an open learning environment in which group interactions and dialogues are stimulated. An open learning environment supports opportunities for extending skills and knowledge by reassuring the freedom – but also the responsibility to learn from mistakes.

- Problem solving

Problem solving involves the knowledge of the complexities in education and learning. We found that leaders for learning had to deal with the demands of being both immediately practical and developing underlying principles so that future problems can be solved (Timperley, 2011). We assert that the professional skill of “problem solving” promotes quality decision making and sustaining school development.

- Using a variety of pedagogical methods

The capacity of leadership for learning is influenced by the extent of the repertoire of pedagogical methods and teaching strategies. We found that the leaders’ knowledge of pedagogical practices and the ability to employ a wide variety of pedagogical method were an important attribution in creating capacity of leadership for learning. The connection between principals and teachers’ leadership for learning seemed captured by the following quote:

“I teach my teachers the way I want them to teach the students” (quote by participant in the project)

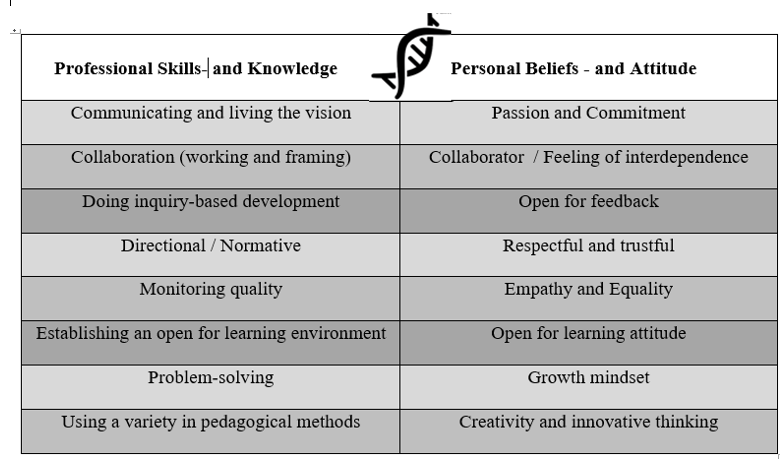

The brick-stones of personal beliefs and attitude

The brick-stones of “personal beliefs and attitude” work in pairs with the brick-stones of “professional skills” (displayed in figure 4). Educators’ perceptions and actions in leading learning are influenced by the way we believe as well as by our knowledge and skills (Stoll, 2016). Together, the brick- stones of “Personal Beliefs and Attitude” and “Professional Skills” create an authentic and personalized capacity of leadership for learning. “If You don’t have the beliefs and attitude you don’t have the skills” (quote by participant in the project).

- Passion and commitment

The capacity for leadership for learning is accomplished by passion and commitment. We found that leaders for learning are prepared to walk the extra mile if it means striving the best to promote students’ learning and wellbeing. Dedication and loyalty to the norm and values expressed in the schools’ visons of learning is in the core of commitment.

- Collaboration and feeling of interdependence

Working in collaboration, you must value “togetherness” high enough to commit yourselves to it. Acting in collaboration depends on you valuing the diversity in perspectives and hold various opinions open for interpretation. We found that the feeling of interdependence and a conscious choice of spending time working together are important components in creating individual capacity of leadership for learning.

- Open to feedback

Open to feedback involves real curiosity and commitment in learning from feedback, believing that feedback is an important information in achieving positive effect. We found feedback to be a powerful catalyst for professional learning and inquiry based development. Seeking both formal and informal feedback from students, peers and formal leader make an important brick-stone of leadership for learning.

- Respectful and trustful

An important part of “leadership for learning” is the ability to build respectful and trusting relationship. We found that working directional and building relationships are not conflicting but instead create complementing capacities. As mentioned earlier, leading learning imply acting normative and directional in regards to the work of students’ learning – the point asserted is that building respectful relationships is the connecting brick-stone.

- Empathy and equality

Leaders of learning must deal with the presence of “power issues” in relationships between the leader and the learner (e.g. principals/teachers and teachers/students). One cannot remove the meaning of power. Thus, embracing and reflecting on the significance of power in the learning-situation is an important brick-stone in the DNA of “leadership for learning”. We assert that monitoring quality may show the positive claim that we as humans are equally worthwhile. Equality and empathy create emotional wellbeing as a motivator for learning and make learners feel valued as a person – despite a current quality.

- Open to learning attitude

Open to learning is a state of mind creating the capacity to engage in and sustain continuous learning. The personal attitude encourage the learner to step outside comfort zones, pushing the boundaries of learning, and maintaining a “wanting to learn” atmosphere in the environment.

- Growth Mindset

We found that endorsement of a Growth Mindset (Dweck, 2014) played a key role in the capacity of leadership for learning. Whether conscious or subconscious, a Growth Mindset creates a powerful passion for learning. As a learner as well as a leader you do not waste time proving how great you are. You believe that you are able to become better and you empower other people to have the same feeling of being able to learn new things and become even better. With a Growth Mindset, you believe in the ability to grow and allow people to thrive and adapt during some of the most challenging times of changes.

- Creativity and innovative thinking

Creativity and innovative thinking are fundamental to all educational activities, and we found it to be an important brick-stone in creating capacity of leadership for learning. In this project, innovative thinking is defined as welcoming new ideas, new ways of looking at things, and new pedagogical methods. Creative thinking is defined as the thinking that enables learners and leaders to apply their imagination to generate ideas, questions, and hypotheses, and experimenting with alternatives to improve students’ learning.

Figure 4: Display: Strands of Brick-stones building Individual Capacity for leadership for learning

Conclusion and final remarks

Though the representations of leadership for learning practices did vary across the four VET schools, we found a substantial coherence in the brick-stones creating individual capacity of “Leadership for Learning”. We assert that the DNA of individual capacity of leadership for learning contains two in-wired strands: “Professional skills and knowledge” and “Personal beliefs and attitude”.

Moreover, the findings of this project revealed that it goes across – not only four different VET schools but also four different countries.

In an increasingly interdependent world, school-to-school learning networks is shown to expand the individual schools’ repertoire of choices by moving ideas and useful practices for school improvement around the EU. This particular project emphasized the importance and value of “Lateral Capacity Building” (Fullan, 2006).

Acknowledgements:

With appreciation and respect for my partners and colleagues in the project-team in “Leadership for learning in VET”.

Photo 1: A collaborative process of playing with data and building knowledge (Helsinki Oct 2017)

References

- Barth, R. (1990). Improving schools from within. san Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Dweck, C. (2014, 93 2). How Can You Develop a Growth Mindset about Teaching. Educational Horizons, p. 15.

- Fullan, M. (2006). Turnaround Leadership. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. (2006, 9:2). Exploring the Principals Contribution to School Effectiveness: 1980-1995. School Effectiveness and Scool improvement, pp. 157-191.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2017 / 2012). Professionel kapital- En forandring af undervisnigng på alle skoler. Fredrikshavn: Dafolo.

- Hopkins, D. (2001). School Improvement for Real. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Robinson, V. (2014). Student Centered leadership. Jossey-Bass.

- Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. (2008, december 44. no 5). The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes. An analysis of the Differential Effects of Leadership Types. Educational Adminstration Quarterley, pp. 635-674.

- Sergiovanni, T. J. (1994). Building Community in Schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Stoll, L. (2016, August 5). Realising Our Potential: Understanding and Developing Capacity for Lasting Improvement. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, pp. 503- 532.

- Stringer, P. (2013). Capacity Building for School Improvement . Rotterdam: Sense publishers.

- Timperley, H. (2011). Realizing the Power of Professional Learning. Berkshire UK: Open University Press.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research – Design and Methods. Thousands Oak California: Sage inc.

siroos says:

Hi your approach about leadership is so beautiful .