During the European Business Summit 2016 in Brussels, Hans van der Loo, former vice-president of Shell, underlined how the scope of changes in recent times is such that it can be defined as the beginning of a new “era”, the Anthropocene. As he focused on the areas of education, training and transition to work, van der Loo stated: “Today we are educating our young people for jobs that do not yet exist, in order to solve problems that we are not yet even aware of. Only few seem to be aware of the exponential reality and we seem to think we can tackle 21st century challenges with 20th century education”. His contribution was then presented again and expanded by van der Loo himself during the third edition of the Conference “Cometa Social Innovation” on 5 May 2017: the change of era that is currently in progress undoubtedly marks a trajectory of change in the education, training and employment sector.

(Co-authors: Paolo Nardi, Samuela Arnaboldi and Barbara Robbiani. Research developed thanks to Progetto GO! funded by the Program Lombardia Plus*)

1. Towards an effective transition from school to employment

Two specific meaningful aspects emerge and indicate an increasingly urgent need to change current educational and training models:

- Obsolescence processes becoming increasingly faster: most of tools and knowledge age faster and faster, just like habits (consumption patterns, work), thus with an evident impact on obsolescence of methods and knowledge and skills required in the labour market.

- Demographic change, amongst other things, significantly affects welfare systems, namely social security schemes. Working age relentlessly increases, but in a context that, as previously mentioned, evolves continuously: activities, tasks, competences that are typical of a job position are hence exposed to multiple changes during the same period of work of an individual; at the same time, the longer employability phase implies that certain tasks cannot always be performed, due to aging. In both cases, flexibility, resilience to new contexts and objectives, and, above all, inclination to lifelong learning become more and more important.

In this respect, the emphasis repeatedly placed by European institutions on introducing entrepreneurship skills and soft skills in training and educational programs makes clear sense, not only for future entrepreneurs but also, and possibly above all, in terms of self-entrepreneurship. By all effects, entrepreneurship becomes a key attribute in one’s own business framework (liability to one’s own goals as well as the company’s), but also in the labour market as the ability to tackle challenges and changes that emerge in everyday life. Self-entrepreneurship may further be read in terms of:

- ability to actively look for a job;

- ability to obtain a job (self-marketing);

- ability to stay employable, even in a context rich with major changes.

Emerging phenomena in society do not only affect the world of work and, consequently, the education and vocational training systems: the very same passage from education to work, the transition from school to employment can no longer be a mere transition phase, but as a key, crucial step requiring a specific educational and training action.

As recalled by CEDEFOP (2018), current difficulties in matching employment demand and supply cannot only be traced back to the so-called skill gap intended as absence of skills currently required by the market. CEDEFOP highlights the wide potentiality of skills currently existing in the job market and that are known recognized/recognizable and hence under-utilized. Such problem is often related to the difficulty by companies to precisely identify the characteristics specific to each job or by human resource departments, to adequately identify the applicants’ potentiality; an exogen contributory element is the rigidity of the labour market, a feature that is still severely present in the Italian context. This specific aspect of the job offer, just like the previous aspect more related to the demand and educational context, demonstrates how urgent it is to act on the transition from school to work as an absolutely relevant step of the process needing deeper investigation, improvement and care through processes that cannot be improvised, neither in school nor in companies. In this respect, CEDEFOP’s report makes it clear how spreading work-based systems alone cannot solve the problem: paradoxically, the phenomenon that appears to be emerging in areas where work-based learning models are in use is that of higher employment, quicker transitions, but lower quality of the labour force in terms of competence.

For this reason, at the macro-level, the role of policy-makers in tackling skill gap and skill mismatch should take the above-described aspects into consideration, so as to guide policies not only to reform vocational training, but the labour market too and, last but not least, the very same transition phase and providers that act as a link of the chain between school and companies.

1.1 A momentous change is in place, also in the labour market

The analysis of the above-referenced context sets the frame for some of the key reasons why the transition from school to work takes on a critical relevance in the current educational pathway of young people, in Italy as well as in Europe.

The problems of skill mismatch and skill gap appear to be the most obvious consequences in terms of self-evident phenomenon. However, these issues need deeper investigation in order to proceed to design a solution. Based on feedback to the European Skills and Jobs Survey (ESJS) dating back to 2014, CEDEFOP confirms that more than 47% of European workers have experienced changes in the work methods and activities performed, and more than 43% have gone through some technological change: lastly, more than 20% fear that their skills will become obsolete in the following 5 years, thus quantifying the emerging skill gap. Further evidence from the ESJS adds on to this data in relation to sectors featuring growth forecasts in the following years: areas of employment where the degree of innovation and a strong customer orientation represent growing factors, whereby routinely jobs are declining in numbers.

At the same time, more than 40% of current workers think that their skills are under-utilized: this is a piece of data that confirms recent research whereby over-skilling seems to be much more impactful than the skill gap (McGuiness et al., 2017).

Over-skilling and skill gap: two sides to the same coin, the skill mismatch, which shows the urgent need for individuals to enhance and improve interaction between education and industry, to the benefit of people as well as of society in general.

Going from Europe’s perspective to Italy’s, the skill mismatch appears to be almost dramatic. About 6% of Italian workers do not have enough competencies and 21% of them have lower qualifications than required. Conversely, almost 12% of employed population is overskilled and 18% has a higher qualification than needed. On top of these 60% workers in a situation of skill mismatch or unsuitable qualifications, you may as well add 35% of workers whose job is not consistent with their course of study. As OECD analysed this data and focused on Italy, the evidence was that “Bringing skills supply and demand into better balance requires more responsive educational institutions and training providers, more effective labour market policies, better use of skills assessment and anticipation information as well as greater efforts on the part of the private sector to collaborate with these institutions” (OECD 2017).

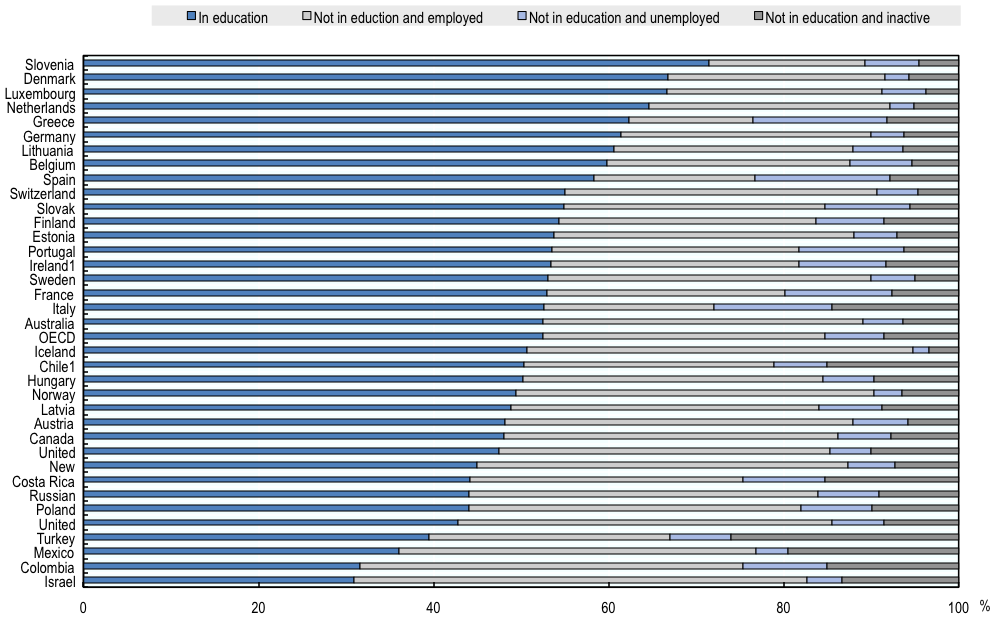

The OECD (2017b) released data concerning the situation of young people aged between 18 and 24 years. In addition to the plague of skill mismatch, Italy must come to terms with another mediocre result relating to the high number of NEETs, which ranks the country amongst the worst performers amongst advanced countries, as you can see in the following table, except for the percentage of young people who are still on an educational pathway.

Fig. 1: percentage of young people (18-24 years) in OECD countries and their situation

Source: OECD 2017b

1.2 From the “end of work” to the “future of work”

In order to get a better understanding of the situation of the so-called generation at risk (ILO) and the tools to help them enter the job market of the future, it is important to understand the direction the very same job market is headed to, as focus of several studies, especially in the area of pedagogy of work. Going back to a nice remark by Passerini (in Dato, 2017) on the works by Rifkin and Donkin, and as pointed out by Massagli (2017), the debate has polarized between supporters of current change as the “end of work” and loss of jobs due to technological change (IoT, Industry 4.0, just to mention a few examples) and, on the other hand, scholars strongly believing in the resourceful ability of mankind to “re-invent” itself, thus putting technology at the service of one’s own creativity. The theory of the “new hourglass” developed by Zamagni (2014) certainly offers an effective image: opposite to the growing majority of scarcely-skilled and underpaid workers is an élite of operators characterized by strong spirit of adaptation and growing competencies. The change we observe in the labour environment.

Different viewpoints have been developed to read the transformation emerging in the labour environment. In this respect, Morgan (2016: 17 ff.) identifies 5 trends:

- new behavioural patterns, dictated by social media, drive to strong cooperation and sharing, new compared to classic organizational theories;

- technology is changing the way we work and the tools we use;

- the Millennials who are used to a new pace and space of work;

- physical and virtual mobility, which contributes to re-organization of work;

- globalization which pulls down previously existing borders and barriers.

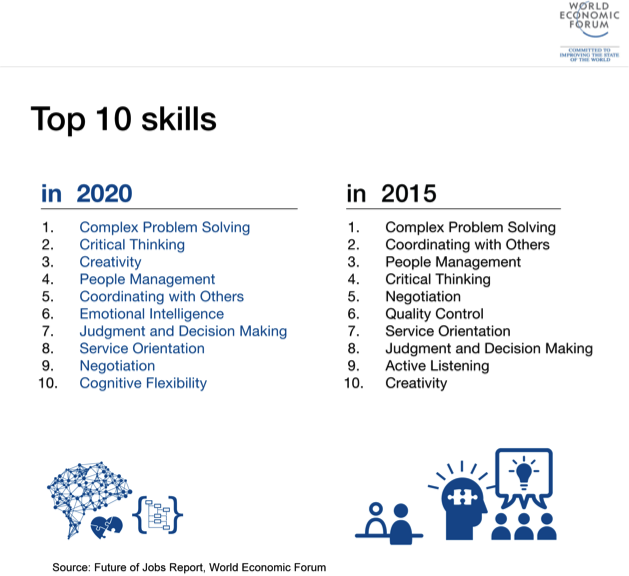

In this respect, Fornasieri (2017a) asks himself: “if what was directly acted by a person is progressively replaced by machines that are even able to perfect their own processes (machine learning); if the data collection and selection factors are operated through algorithms also when it turns to hiring human resources (Dagnino, 2017), what is left as human-specific and unreplaceable factor? We believe one of these factors is creativity (Seghezzi, 2017) whereby we mean the ability to activate one’s own genius, drawing on one’s own way of seeing and thinking which can put forward experiences, ideas, solutions, intuition, visions with a key common denominator: these are not mere logical outcomes of previous processes, they are indeed jumps ahead, discontinuation from knowledge and production”. The World Economic Forum (2016) itself has recently recalled the growing importance of creativity which went from number 10 in 2015 to number 3 in the ranking of the top ten skills for the labour market in 2020.

Fig. 2: the top 10 skills in the future

Source: WEF 2016

Digitalization of work processes, progressive task automation, growth of data quantity has reached such an extent that they cause the most peculiar human mind abilities to re-emerge as unreplaceable by new digital devices. Paradoxically, as the complexity of technological-digital systems underlying work processes increases, their unpredictability has also increased. What makes qualified workers unreplaceable today is their personality, made of experience, knowledge, competence and, above all, creativity, exactly by effect of an increasingly complex system which changes continuously and unforeseeably. In this respect, one may just have a look at the key founders, partners and CEOs in companies such as LinkedIn, YouTube, Pinterest, PayPal, Palantir, Alibaba, Airbnb, whose background does not include IT engineering programs, but rather degrees in philosophy, design, literature, history of the Middle Ages, social sciences (Fornasieri, 2018). This evidence appears to confirm that what will really make the difference soon and hence guide future processes, will be people educated in “classic liberal arts”, “Humanities”, thanks to the power of cultural vision embedded in them and required by the globalized world.

In conclusion, Dato (2017) identifies 3 “key motions” that will orient the pedagogy of work and, for this reason, all efforts relating to transition from school to work in a broad sense: openness to new technologies; tendency to sharing; self-entrepreneurship. The latter concept is more appropriately developed by the author in terms of proactivity and human agency, meaning the ability to play the starring role in the reality we live in, with spirit of initiative, self-management and self-marketing: the combined set of soft skills which stand out, amongst others, as increasingly more critical even in the innovation process of educational pathways. As a matter of fact, these abilities need to be trained and constantly developed by the young person on his work pathway, which is inevitably a dynamic one: the concept of passage from job-oriented to career-oriented training (Nardi, 2017) or, more precisely, in the form of boundaryless careers o protean careers (Hall, 1976).

We are undoubtedly at the onset of a new pedagogy of work, a paradigm shift (Alessandrini, 2017). Specifically, as Dato says (2017: 268), “work is then to be designed and built, starting from a vocational development project which is sowed over the years but also thought, imagined and created beyond the boundary of present time […] An integrated model appears to be traceable in the humanistic management, (one that systematically combines training and work and establishes continuity between school and enterprise), one for «good training» and one for «good enterprise »”: in this respect, school-work transition is much more than a moment or going-through phase, pedagogically it still requires a cultural process of diving-into things and side-by-side counselling which will become a habit for the future worker.

2. Legal framework and laws

The strong focus placed on employment in Junker’s Plan and recently released documents by European institutions show the scope of concern by policy makers about the topic of unemployment and roads how to improve the employability of young people. The focus of the EU New Skills Agenda (EC, 2016) is indeed placed on the development and spreading of work-based learning as the most effective way to respond to the currently existing skill mismatch. In addition to this, however, there are other recommendations relating to the time of transition from school to work and the framework conditions which should be worked upon (Nardi, 2017). Firstly, one of the primary recommendations by the Agency calls for promotion of resilience as part of the educational pathway with the aim to “equip everyone with a broad range of skills which opens doors to personal fulfilment and development, social inclusion, active citizenship and employment. […] There is growing evidence of the benefits that higher levels of entrepreneurial attitudes and skills can bring. […] Entrepreneurial skills have also a more general impact on the employability of young people, contributing to higher employment rates” (EC, 2016).

The ability to understand skills (skills intelligence) is a second factor that the Commission intends to foster in order to enable young people to not only know but also adequately communicate about their skills; conversely, this helps business companies to assess their needs and effectively recruit staff. Working to enhance skills intelligence is not effective without the cooperation of different players in education and labour market: schools, companies, public institutes and research community, from local level to the national and international one.

Monitoring the placement of VET institutes’ Alumni is another item the Agency places particular emphasis on: it is a tool that allows, ex post, to evaluate the quality of education delivery and to identify opportunities for improvement. School-work transition, in addition to training, may remarkably benefit from monitoring the placement of young people, thus delivering data on the quality of the placement service.

2.1 Italian framework

By Ministerial Decree nr. 139 dated 22 August 2007, the Italian Ministry of Education, has codified the Citizenship soft skills by drawing on the European legal requirements for Key Skills for lifelong learning and put them in a document featuring the following definitions (Fornasieri, 2017b). In line with the advent of new skills for world of work and inclination to human agency (Dato, 2017; Nussbaum, 2011), the following is to be pointed out:

- Learning how to learn: to organize one’s own learning by identifying, choosing and using various sources and ways of obtaining information and training (formal, non-formal and informal), also in accordance with available time, one’s own strategies and one’s own method of study and work.

- Design: to develop and implement projects regarding the development of one’s own activities of study and work, thus making use of knowledge learned to set meaningful and realistic goals and related priorities, thus assessing constraints and existing possibilities, defining strategies for action and verifying achievements.

- Communicating or understanding messages of different nature (everyday, literary, technical, scientific) and complexity that are conveyed by using different language (verbal, mathematical, scientific, symbolic, etc.) through different media (paper, IT and multimedia) or represent events, phenomena, principles, concepts, rules, procedures, attitudes, moods, emotions, etc., etc.

- Collaborating and participating: to interact in a group, thus appreciating different points of view, enhancing one’s own and others’ abilities, managing conflicts, contributing to common learning and implementation of collective activities in acknowledgment of the fundamental rights of others.

- Acting with autonomy and responsibly: to be able to actively and consciously introduce oneself into social life and getting one’s own rights and needs through whilst recognizing those of others together with common opportunities, limitations, rules and responsibilities.

- Problem-solving: to tackle problem-prone situations by building and verifying assumptions, identifying sources and adequate resources, collecting and evaluating data, putting forward solutions and use of contents and methods from different disciplines, according to the type of problem.

- Identifying connections and relations: to identify and represent connections and relations between different events and concepts through consistent reasoning, also belonging to different disciplines and far in space and time, thus capturing their system-based characteristics, similarities and differences, consistency and inconsistency, causes and effects and probabilistic nature.

- Acquiring and interpreting information: to acquire and interpret information received through critical thinking in the various settings and through different communication tools, thus assessing its dependability and usefulness, distinguishing facts and opinions.

- Although it has never been explicitly mentioned, creativity appears to be connected to the development of all these skills, as a deep tissue that stimulates learning processes. This statement also rests on philosophical and scientific data as well as quotes by Einstein: “The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination”.

3. School-work transition in Cometa: the development of the EU Employment Office

Cometa Formazione’s Employment Office (EO) was set up at the service of training of young and adults and has then become an accredited employment services office, with a specific focus on integration between school and work (internships, apprenticeships) and counselling young people in the transition between school and work. More specifically, the EO’s function is to bring the culture of work to school and that of school to the labour market, thus fostering communication between these two worlds. Therefore, the goal is education of responsible individuals who are aware of their uniqueness and richness and ability to become part of the productive system. The relationship between school and business companies, aimed at ensuring professional success of the individual, is, in Barbara Robbiani’s words (expert of the EO), “a bridge from school to work and work to school, through the creation of a circular system which conveys learning and growth needs through a structural connection between enterprise and school, offering learning pathways, situational counselling and integration in the labour market. In order to build this area of conversation and confrontation, we believe a constructive and holistic view of the student is required: the company sets forth the needs while the education institute fills the task of rearranging those needs into learning pathways. Together, school and enterprise, make it happen, through co-teaching, co-design, internships and integration in the labour market”.

To such end, there are different stakeholders the EO talks to in carrying out its operations:

| Category (Specific stakeholder) | Goal and activity | |

| Target | Students attending educational and vocational training programs | Alongside tutors and teachers, the EO deals with identifying the best business solution for the internship (curricular and extracurricular), to allow students to enhance/upgrade their weak skills or consolidate their strengths. |

| Former students looking for a first or new job | At the heart of school to work transition, the EO guides young people into the job market through a structured process. | |

| Unemployed people looking for new job as identified by the employment centres or institutions | Through ad hoc schemes (Youth Guarantee, FiXo) and intense cooperation with the school itself, the EO sets out a plan to recover self-esteem and then identify a work solution that will be monitored during the early stages. | |

| Foreign young people needing reception pathways and seeking their first job | Alongside social partners and the school itself, the EO offers foreign young people (often unaccompanied minors) a basic educational program and an internship, thus facilitating “normalization” of the precarious situation this group of beneficiaries is often faced with. | |

| Chartered accountants, business consultants, school principals | In recent times, competencies acquired by the EO are at the service of the community of chartered accountants or business consultants that are interested to dive into the rules and tools of work-based learning or training apprenticeship. Schools themselves are often interested in getting to know the EO’s operating methodology from an educational and organizational perspective. For this target, training sessions are organized in Cometa or at the headquarters of the company/school itself. | |

| Partner | Enterprises | The relationship with business companies is seen as strategic to the everyday operations of the Employment Area. A stable and constructive connection favours companies’ awareness to be an educational partner to Cometa and allows the Employment Area to bridge between business needs and the school community, in addition to developing commercial strategies related to integrating former students in labour market. |

| Training institutes – tutor | In the interest of the young individual, a clear educational pact between the company and the school is always supporting the experience of work-based learning. Drawing up and monitoring such individualized educational pact results from cooperation with the training staff and, specifically, with tutors who share the road of the young person daily and can therefore better identify the most suitable work experience. Ongoing support and training activities are also provided to tutors who will learn how to deliver coaching in the field, thus putting forward proposals and new ideas to be pilot-tested in order to steadily increase the effectiveness of their work. | |

| Institutional and social organizations | Cooperation with public institutions, both local and European, is crucial to establish the legal framework to operate in for the EO and the flow of available financial resources. | |

3.1 Getting ready to transition from school to work: Internship TU

As outlined in the previously detailed context, transitioning from school to work cannot be reduced to a mere passage. The key task for the EO within Cometa Formazione is to support a cultural process of personal growth and development through the experience of employment counselling, from the very first internship experiences. In this respect, cooperation with the school, namely with tutors, is crucial: maturing to a new cultural concept of work and self-entrepreneurship is indeed fostered with a stand-alone training unit, the so-called Unità Formativa Stage (Internship Training Unit), which is developed in synergy by the EO’s staff and tutors; the latter then take care of the real implementation by preparing and completing the traineeship and ensuring shared monitoring of the same.

The paradigm shift experienced by society and detailed in previous pages has more than a meaningful impact on the labour market. Active job-seeking abilities as well as “staying employable” over time require individuals to be increasingly trained to handle self-management and responsibility. To address this challenge, a program was started back in 2011 at Oliver Twist School under the name Internship Training Unit (Internship TU); it aims at integrating and accompanying the experience of three traineeship periods in a company (one per year), starting from the second school year.

Work in a company is seen as having high potentiality in the area of individual orientation as it enhances practical knowledge of class-taught notions, filling them with meaning and value; it allows to get to know the market and its various occupational contexts, it increases and strengthens self-awareness during years of growth and change.

In consideration of the difficulties young people have to face during their first year at secondary school to get into and adapt to the new context, Cometa’s Oliver Twist school introduced the curricular subject matter of Internship TU starting from the second year with the aim to accompany the student to self-discovery and discovery of the world of work through a process that enhances not only technical professional skills but also a new ability: to learn how to look for and find a job. This means learning how to navigate in the labour market, that is being able to communicate effectively, thus promoting one’s own skills and establishing a network of relations and useful connections over time to get referrals and multiply valuable occasions by word of mouth.

Training delivered through the Internship TU is introduced to the class by relying on remarks, experiences and evidence that help students understand the relevance of starting to look for a job in the area or activities involving one’s own highest personal interest, which should be identified and become a focus of the orientation process. Thus, students begin to design their professional future, followed and supported by a tutor who acts as a real coach and takes them through a conscious effort of thinking in long-term perspective, whereby one needs not only to be up-to-date and improve to live up to the expectations of the companies, but also to become the protagonist of one’s own life. Protagonist is to be intended as self-fulfilled, able to orient and re-orient in a lifelong learning perspective which revolves around three principles: freedom, self-determination and responsibility in the complicated process of interaction between individual and reality whereby the individual is expected to make choices.

- Freedom intended as “breadth of perspective”, which allows to look beyond the limiting boundaries of one’s own mental and behavioural patterns;

- Self-determination intended as the opportunity to choose and make decisions whilst staying closely connected to the essence of one’s own identity;

- Responsibility, finally, as the <ability to respond > to reality, consequence to opening to reality, being able to capture that “everything is there for itself” as an occasion per se and, therefore, being able to respond by sticking to it.

Freedom to be open to new life experiences beyond patterns and habits, self-determination intended as making conscious decisions based on one’s own feeling, being responsible for one’s own actions: this is a key self-awareness pathway to achieve the goal of personal fulfilment. In this way, a young individual manages to progressively find out and perfect knowledge of self that brings to the surface what Cometa defines as the in-born excellence of every human being.

If “becoming the protagonist of one’s own life” is the ultimate goal of the Internship TU, and freedom, self-determination and responsibility are its guiding principles, its key tool is the development of awareness: «as a matter of fact, one cannot become the protagonist of one’s own life unless one knows oneself and the surrounding reality. Not knowing oneself means to ignore what one really wants, thus becoming, per se, a preliminary hurdle that precludes the very same chance of self-fulfilment, possibly due to lack of “contents” one may say; not knowing reality – that is to say, how it functions, its rules and laws – means to direct many choices to failure, or to partial success, thus extensively jeopardizing one’s own goal of personal self-fulfilment. Awareness – that is knowledge of reality of one’s own self (“heart”) and discovery of one’s own “excellence” and the surrounding reality – is therefore a key and essential tool to become the protagonist of one’s own life».

As to the method to develop necessary awareness to achieve this goal, it once again coincides with the method Cometa has adopted as its steady guideline in all its projects: «reality-based learning» (Mulder, 2018). Hence, the centredness of internship (or traineeship) as part of developing such a program: all the activities are deployed from experiences made during traineeship in the company or at the service of it.

3.1.1 Internship TU: the method of “gradual engagement”

In practical terms, the application of such a method requires gradual engagement by students in their awareness process, at the completion of which they should be fully entitled to act as protagonists of their educational and professional pathway.

As part of the Internship TU, everything revolves around the traineeship, therefore the gradual engagement of youth concerns this key core experience.

The engagement process is gradually completed with three steps: Orientation, Specialization, Professionalization, which correspond to responsibility going from the tutor to the student who then plays the leading role in his/her pathway and choices.

“Orientation” is the topic of the first year of traineeship which corresponds to the second school year. The purpose of the first traineeship experience is for the young people to orient themselves, to develop the ability to get to know themselves and reality, namely the world of enterprise. Given their young age, this is the primary aim of the contact with the world of work. Students, therefore, are not so much required to learn a job and be productive, but rather to learn how to live at a workplace: that is to say, to get an understanding of the purpose of rules and complying with them; to learn how problems are tackled or relational problems are solved; to learn the names and definitions of various departments and professional roles; to get an understanding and develop an interest in the history and mission of the company; to realize how communication occurs and which work teams are there as well as the product-making process in its different stages. In other words, the ability to lift the eyes from the merely assigned tasks and look at whatever is constantly going on around that is integral part of the assigned task and fills it with meaning, interest and taste for discovery.

The topic of the second year of the Internship TU is “Specialization” and calls for the students to take on the risk of choosing their specialty. This implies to be able to critically “read” the traineeship experience of the previous year and one’s own work in the school’s apprenticeship studios (botteghe) and ask oneself “which work” they feel more inclined to, in fact to start thinking about a “professional vocation”. The responsibility lies in facing the risk of choosing a specialty and applying it to the company where traineeship will take place. This means that students will learn how to draw up their CV as well as the meaning and relevance of this key tool in the labour market and they will also learn how to go through a “job interview” in a company.

The topic of the third year is “Professionalization”: the purpose of the last year’s program is to fully define the professional profile of the student and learn a methodology to actively seek employment. Based on thinking over experiences and knowledge of self-acquired in the previous two years, students are offered the chance to formulate a grounded request for the job they’d like to fill on their traineeship, but also the company where to complete it. Ahead of looking for a job, it may as well be possible that their motivation lies in wanting to dive into a specific task or enhancing one’s own CV with a yet to be completed specialty. Moreover, in consideration of the company information collected in the previous years through their individual experience or their classmates’, students can select the company that best fits them or the task they want to perform or the best opportunity to access the labour market upon completion of the traineeship.

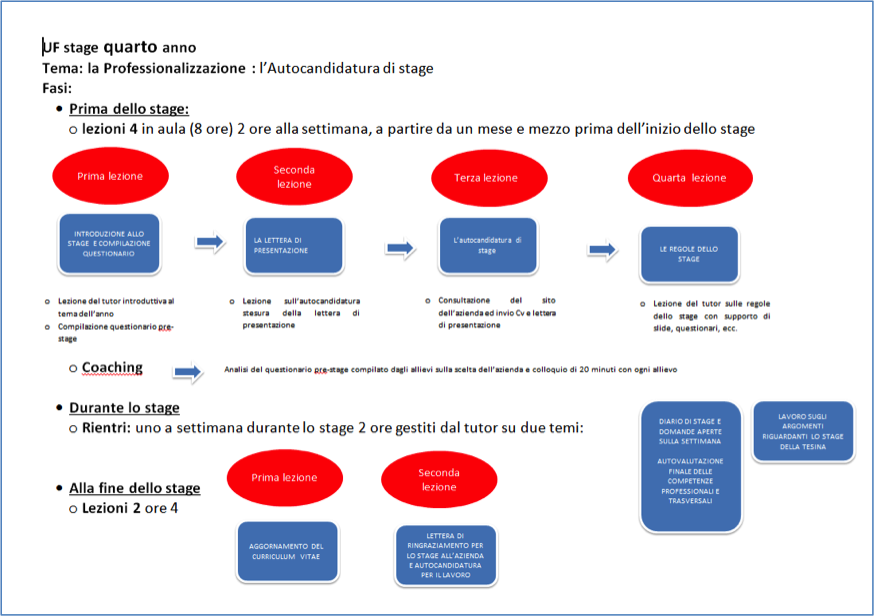

Starting from 2015-2016 a pilot-test program was introduced and then continued in the following years: all fourth year students prepare and submit their self-application by drawing up a cover letter and readjusting their CV based on the specific characteristics of the company they’re applying to and by going through an “internship interview” which closely resembles a real job interview.

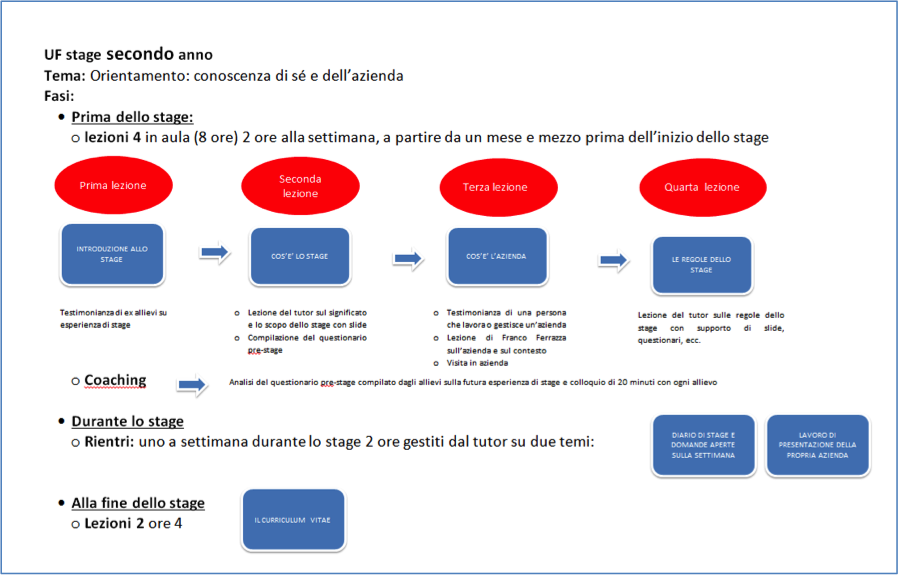

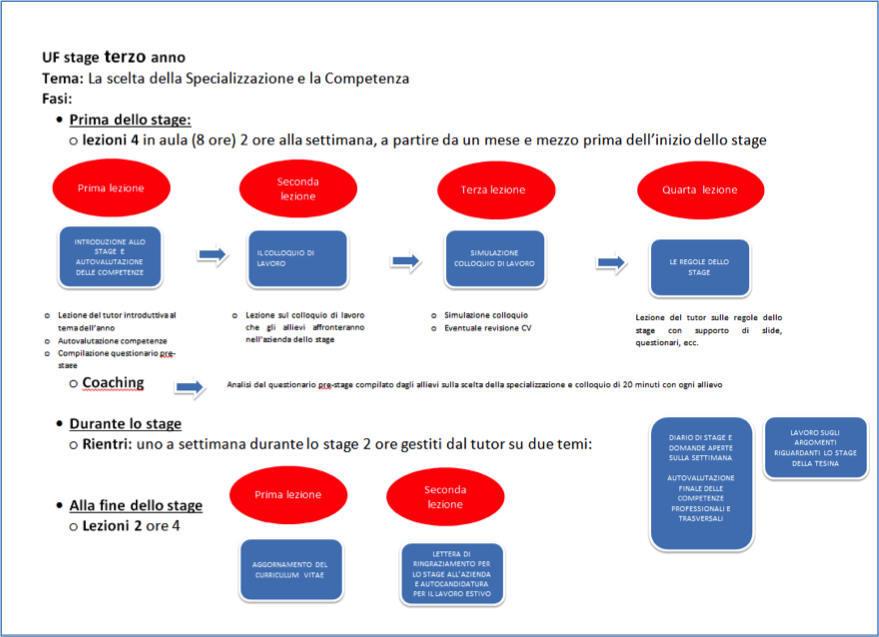

The following tables include a summary of goals and activities that are gradually put in place according to each academic year.

Figure 3: topic and scope of contents of Internship TU for the second academic year (internal source)

Figure 4: topic and scope of contents of Internship TU for the third academic year (internal source)

Figure 5: topic and scope of contents of Internship TU for the fourth academic year (internal source)

3.1.2 Contents and learning tools of the Internship TU

Cometa’s methodology does not resort to classroom-taught lessons, it rather makes use of “tools” calling for active involvement of students. Learning tools may vary, evolve and get renewed continuously so that they can really serve the various purposes that are to be achieved each year and that relate to the specific point in time of the internship program: before, during and after internship, learning tools have to be aligned to the aims of the lesson, to the classroom characteristics and to the ability and sensitivity of the teacher using them. The teacher and “film-director” of the class hours is the tutor.

Lessons prior to internship

Regardless of the Internship TU year, learning tools are activated in different fashions every year prior to internship with the aim to prepare the students. The specific goal, at this stage, is, on the one hand, to design the internship, whereby students give their increasingly bigger contribution as they grow and make experience and, on the other hand, to engage them and, consequently, get them to take on responsibility so that they can experience the internship as fully prepared as they can be. One month and a half prior to starting internship, 4 specific lessons are delivered in classroom depending on the goal set for each specific year.

The first and third lesson of this program are an introduction to internship and are presented by testimony rendered by other students, so that students can start to develop an idea of what it is about. To such end, a meeting is organized at school, thus inviting both senior students who have already made that experience as well as individuals who found self-fulfilment at work intended as the focus of the internship, or specialists that are professionally exposed to the business context. By so doing, students can see the experience from two different viewpoints: one is the perspective of their peers, which somehow will be close to what they may experience too; the other is the perspective of adults who have already been working for a while, which can provide them with a sort of “depth of field”, a long-term outlook that can help them relativize the first impact and visualize and decode the world of business and work through their eyes.

The second step is devoted to becoming aware of the meaning and relevance of traineeship in the educational pathway of any given student. The tool that is resorted to is coaching delivered by the school tutor. Each tutor will personally coach each student of the classes she/he’s in charge of and help them define their goals, become aware of personal motivations behind the traineeship aside from school obligation.

Coaching is delivered in two different fashions: the first is a letter or questionnaire (depending on the tutor’s preference) that he/she administers to each student to ask questions that will ultimately lead to voice the student’s lived experience relating to the traineeship (the selected tool fosters inner thinking through reading or writing and therefore fights against the student’s tendency to reply instinctively or to “elude” direct questions with vague answers); the second opportunity is an individual conversation whereby the tutor and the student jointly review the answers, so as to clarify their meaning as accurately as possible.

The letter or questionnaire change from year to year depending on the specific goals pursued by the Internship TU, but the questions relate to the following themes:

- personal motivation for the internship;

- personal and professional desires and goals;

- acknowledgment of already acquired skills and identification of skills to be developed;

- voicing difficulties and fears;

- preferences about the specialty (second year)

- preferences about the company (third and last year);

- request for help.

The coaching interview, whereby student and tutor jointly review the answers to questions raised in the letter or questionnaire, opens a conversation that will be continued by the tutor during “company on-site visits” that will be periodically made throughout the traineeship duration.

The fourth lesson, a very important moment of the program approaching the traineeship during the first year, focuses on the explanation of the internship rules.

It is key for the student to realize that some implicit, i.e. unwritten, rules are applicable in a work environment and they differ from rules defining more informal contexts where students have navigated up to that moment. Upon getting into a company, such rules are already acquired, at the expense of causing embarrassment and negative evaluation by the company and future co-workers.

During the third and fourth year the same lesson is delivered every year upon completion of the internship preparation program until the tutor deems it appropriate according to the needs and knowledge of the class; it will rely on more accurate tools and group lesson, brainstorming and mutual exchange to finally draw up the “ten golden rules of the class internship”.

Learning tools during internship

Once the preliminary internship preparation phase is completed, the real activity at the assigned company will start. The internship purpose varies according to the academic year:

- II year, orientation, that is knowledge of self and reality. It goes without saying that this need is strongly felt especially at the first year as students have no idea what an internship is about; the goal, therefore is exactly to prepare them to the experience.

- III year, specialization: choosing one’s own specialty and teaching students how to relate to the company; hence, the need to learn about the key tools of initial communication with the company, that is to say CV and job interview. As far as the CV is concerned, an effort is made to put the greatest possible emphasis on its meaning and value, both for oneself and whoever receives it, without conceiving it as a “shopping list” to be mechanically ticked off; in fact, it is an extremely important tool to obtain knowledge of self, very useful to the reader as the latter can realize the ability and characteristics of the person writing it. The same applies to the job interview: after introductory lessons to the tool and a classroom simulation, students are ready to go through it in the company they’ve applied for as trainees. It is important to underline this part of the request because as you teach to “ask for”, it is implicitly conveyed to students that a company granting an internship place is providing an opportunity to learn.

- IV year, professionalizing the students, that is to say to develop their ability to present themselves to company to obtain a job, with an updated CV and the opportunity to refresh how to face a job interview; above all, two additional steps are added and represent the fifth stage, which is overall termed self-application: collection of information about companies and drawing up of the cover letter (with subsequent update of the résumé depending on the specific features of the company where one plans to apply). Once complete information has been collected, students are supported to carefully go through it so that they develop a clear idea of the activity performed by the company and how it is performed, as well as the perspective professional role the company may need to fill. There is one point we frequently discuss with our students in class as there isn’t one single CV that is good across all companies: there is a résumé that needs updates and acts as the “baseline”; it then needs finetuning and readjusting according to each application so that both CV and cover letter build up one single, consistent body, with no repetitions nor information the specific company may not be interested in.

Learning tools that are applied during the internship pursue a twofold purpose: to help student come to terms with the experience they’re going through and focus on what they’re learning and, on the other hand, to involve the company in the educational project of the young trainee.

One of the most useful tools in place especially during the first year is the Internship Diary. It is drawn up by students on their back-to-school day every week, under the supervision of their tutor who helps filling it up. The aim of the diary is to help students sum up what has happened during the latest internship week and identify the highlights: this way they can “time out” and pay attention to what is happening. Without this sort of “alarm bell” the risk would be for weeks to pass by under the impression of doing “the very same thing” over and over. As a matter of fact, that is never really the case; as you really pay attention, no single moment is the same as the other and each time the same operation is repeated, there are endless variables hiding in the focus of the activity as well as in each individual, that is to say a person who is growing, evolving and making use of the latest experience to relate to the task to be fulfilled and the people working with them and the customer. Therefore, the Internship Diary helps us Stop and Think About what has happened during the week to “find out” the “newness” in every single moment, particularly skills acquired and difficulty emerged.

In addition, students are required to look for information about the host company, not only in terms of products and service delivery, but also in terms of internal organization (departments, professional roles, organizational chart) and work methodologies, culture and corporate rules. Understanding that each job in a company has a meaning is an important aspect when it comes to train a junior professional. Each job completed has a “before” and an “after” and builds into a logical process that is to be understood. No-one can limit oneself to “do one’s own bit” without feeling part of a “system” process that needs to be understood and owned. For this reason, it is important for a student to be guided to paying attention to the entire company, understanding the flow of the product, the professional staff involved and the communication system amongst various departments. What is the ultimate purpose of the company in consideration of how it intends to be in the market and, therefore, what practical implications this has on each worker.

The third key tool in this stage is represented by periodical company visits by the school tutor for the benefit of each student. These visits perform a variety of functions such as to avoid leaving the student to his/her own devices in an environment that is initially foreign to him/her. In this respect, the main function is to accompany the student to put him/her in the best conditions to perform at his/her best, thus favouring both the young person’s and the company’s interest. Moreover, company visits serve the purpose of involving the company in the educational project Cometa developed around the student. In other words, it is about making the company aware that the internship doesn’t just pursue the aim to teach a young person how to perform a certain task, but it is first and foremost an educational experience. Therefore, a student will complete his/her traineeship knowing how to perform a certain task but also with much more extensive knowledge about the real life of an enterprise: in fact, the internship is an educational methodology which integrates with the traditional one in classroom, and, hence, it deserves a wide-open outlook. If any difficulty emerges during the internship and the student does not know how to tackle it, the school tutor who directly communicates with the company tutor the student has been assigned to will usually enable him/her to quickly solve issues that may turn into insurmountable impasse.

The fourth and last tool in this stage is represented by the internship report (for first year students) and by a dissertation (for second and third grade students), respectively for the professional qualification of “operator”, that is to say “technician”. As far as the internship report is concerned, it prompts students to provide a detailed picture of the company they did their internship in with the twofold purpose of helping them get an understanding of the key information that characterize a company and stimulate them to appreciate the meaning of the role they filled in the manufacturing process they’ve taken part in. The internship report usually develops along five points, thus requiring students to provide some key information relating to the host company, staff, safety at work and environmental-friendliness, product, customer profile. For students of the catering training course, another section in English is also required whereby key information shall be provided in English.

Learning tools after internship

Tools that are applied upon completion of the traineeship have the primary function to help treasure the experience and, hence, integrate all the lessons learned throughout it. They mostly include tools to evaluate abilities and skills acquired by the trainee: it is not merely a detailed list-like survey of all aspects discussed or experienced, but a real measurement of the extent each of them is owned.

The evaluation is completed in a very extensive and in-depth fashion as it concern both technical-professional skills and soft skills: the ability to relate to colleagues and supervisors – and, therefore, the ability to collaborate and participate in team work; the ability to ensure accurate execution of work by complying with timeframes, procedures, tidiness of workplace and, on the other hand, by keeping tools in perfect operation; the ability to control the assigned work process whilst recognizing mistakes that have been made; and, more generally, the ability to communicate effectively, resourcefulness, spirit of initiative and creativity.

The self-evaluation by the student makes use of two instruments: a radar chart for technical-professional skills and forms or questionnaires prepared by tutors. The scores have the following meaning:

- Never done or I can’t do it;

- I’ve seen it demonstrated;

- Done with supervision;

- Done without supervision;

- Excellently done

3.1.3 Value and impact of the Internship TU

Although it started off as a pilot-test, the Internship TU today stands out as one of the key pillars of Cometa Formazione’s learning offer and a key tool to develop a work culture that makes transition to employment a smarter process. There are different aspects that are key to the success of this educational tool. It certainly contributed to make student orientation more effective and real: the internship is an excellent means to test one’s own talents and essay one’s own attitudes. Secondly, though very gradually, the Internship TU combined with the work done by the tutor allows to learn how to look for a job. The fact that it develops along three years allows students to “deposit” progressively all relevant information relating to how to establish and maintain relations and communication with business companies: the main consequence is an increased capacity to properly approach the work environment, its rules and values.

The co-responsibility educational pact and collaboration between the enterprise and school and, obviously, the trainee, add effectiveness to the traineeship experience, at a point when it may as well be that a trainee is hardly noticed in a company or is perceived as a cost item. The company is not only aware of the trainee’s presence, but it takes part in the educational task of the school by making a commitment to the student’s pathway and, for this reason, by fostering chances of the student being hired upon completion of training.

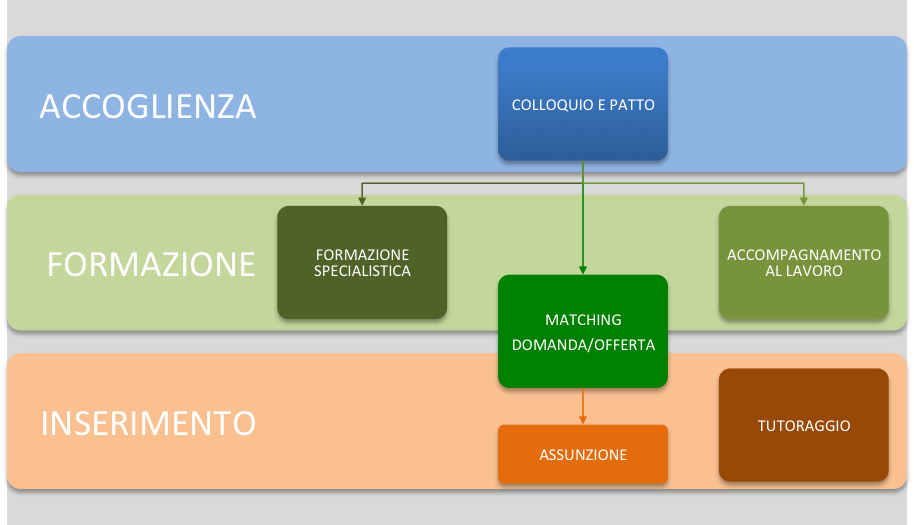

3.2 Inside work-to-employment transition: the need for an “educational pact”

In addition to accompany Cometa Formazione’s students along their training activities, the EO accompanies students to employment upon obtaining their qualification as well as young people and unemployed or migrants. These activities represent the second pillar of work-to-employment transition, once again according to a well-defined process where positive results are continuously monitored. The so-called Employment Branch office for adults, is therefore aimed at providing employment counselling service to former unemployed alumni in the first place and secondly to job seekers that apply for such service. Counselling implies various steps and activities that are differentiated also by target: hence, it is a real educational and training pathway, a free-of-charge counselling offer the students can freely join by “actively” committing to seeking a job.

Between twenty and thirty students averagely attend the program every year, they take part in it and set themselves at play, through tangible and active work that is done both in team as well as individually and raises their awareness and knowledge of self; sometimes a young person needs to find the energy and motivations required to effectively address his/her personal job-seeking effort. For this reason, flexibility plays a key role, though as part of a well-defined process: practical and technical information is under continuous update and it is delivered in a fashion that is adaptive to the degree of maturity and experience of the young person. The program develops along various moments where each student is guided to go through an introductory job interview down to the definition of a skill balance, management of the relation between desire and reality, drafting of an effective CV or an individualized cover letter, whereby the student learns about the relevant use and value of these tools at a first employment contact, registration with temporary employment agencies, visits to a labour exchange office; active search for companies in the surroundings through specialized internet web sites, online databases, newspapers. Classroom activities are also open to comparing each other’s experiences, sharing difficulties, but support and guidance by the teacher do build a sense of self-trust that changes people and makes them more effective during a job interview, promoting their application, presenting their own experience. Nothing is ever taken for granted and students are prepared to gradually get to know the labour market without concealing any of its difficulty or complexity, but rather teaching them how to consciously and effectively tackle them, understanding the value of different viewpoints, that is one’s own and the employer’s or that of a staff recruitment agency.

The key point, ever since the very first meeting, is the signature of a “pact” with the young person: in line with Cometa Formazione’s pedagogical approach, no educational or training initiative can be received passively without this diminishing effectiveness of the effort. Therefore, the young person is requested to underwrite the joint building of a counselling pathway which calls for his/her responsibility, spirit of initiative and proactivity.

Figure 6: scope of post-qualification activities of the EO

The very first step for every young person is reception. “Receiving to work” is the mission that consolidated over the years as a distinguishing factor of the EO’s work methodology. For students graduating from the school, the dimension of reception takes the concrete shape of a meeting held by the two managers of the office in each of the last year classes to explain what their job is about and invite students to start their employment-to-work transition pathway. For young unemployed or NEETs, receiving the person implies sharing their difficulty over the period of unemployment: meeting with them allows to get to know each other and establish a contact to design more targeted actions to tackle the problem underlying unemployment conditions, both from a general as well as an individual perspective. The goal is therefore to lead a young person to address his/her unemployment condition in a conscious, active and positive fashion, as an opportunity for growth, learning, knowledge of self and reality in the light of adjusting and changing in response to the needs of reality.

The micro-goals of the first interview include:

- knowledge and introduction of the operator, the service and, if necessary, Cometa;

- introduction to the purpose of the employment office, its operating procedures and the underlying concept of service delivery;

- verification of the interest into participation on behalf of the recipient;

- verification of the opportunity to register with regional school allowance scheme (Dote regionale);

- diving into the personal and employment situation of the recipient;

- underwriting the co-responsibility educational pact.

The EO staff have prepared an intake interview form (see enclosed document) which is useful to collect and subsequently record information resulting from the interview as well as personal documents, in a personnel file.

The outcome of the first interview leads the EO staff to outline a possible roadmap which includes three options:

- Immediate matching with open positions offered by companies;

- Delivery of extra training:

- Identification of a specialty training program;

- Accompaniment to transition.

3.3 Extra training activity at the service of school-to-work transition

Extra training stems from the need to equip young people with necessary skills to adequately integrate in the labour market. Skills can be specific to a certain working area: in such a case, jointly with the school, the EO orients the young person to housekeeping, food & beverage, dining room service, photoshop training courses, just to mention a few. In this case, the offer evolves continuously: availability of funds, market demands, demand analysis by perspective recipients are the key variables. The relation with companies is key to collect available training internships within these specialized pathways.

As an alternative option, or after this stage, the EO provides the young person with proper support to transition to employment structured into several theme-specific meetings that are defined according to a specific plan:

- drafting of a skill balance;

- teaching of active job search;

- intermediary action with companies;

- employment counselling;

- tutoring during early employment phase.

3.3.1 Skill balance

After signing the pact, on the second meeting, EO staff help the young person make a list of his/her skills and prepare a CV, that is to say the tools to dive into deeper knowledge of self; these tools are also utilized to identify potential chances of labour market integration founded on individual skills and characteristics (pain points and excellences). Micro-goals of this activity, sharing self-awareness as common trait, include:

- To recognize and become aware of one’s own skills, knowledge, abilities, personality traits, desires, motivations, expressed both at work as well as in life as part of a unity of self.

- To identify various types of professional profiles in addition to pre-set ones, which one can apply for based on competencies.

- To learn how to mobilize skills on each working task.

- To identify job-seeking areas.

Here too, certain defined tools can be resorted to: from the format to list skills adopted by the Region of Lombardy to the psychological-inclination evaluation form developed by the EO itself; the form featuring “concentric circles” developed by Barbara Robbiani allows for a first pondered approach to seek a job.

3.3.2 Teaching how to actively seek employment

This learning module was created to develop and support the ability of an individual to actively look for a job through educational and training goals that are focused on excellence and creation of adequate job-seeking tools (CV, cover letter and job interview). In short, the intent is to enable a young person to successfully go through the transition to new employment, thus offering skills to be redesigned and utilize the said tools independently. In this respect, autonomy in job-seeking is fostered, as well as the sense of responsibility and self-responsibility, enhancing the ability to make plans, communicate, obtain and reprocess information. Micro-goals relating to active citizenship skills in the labour market can be summarized as follows:

- To accompany and support the job of seeking employment;

- To conduct active job search in a responsible fashion by confronting uncertainty;

- To realistically recognise one’s own value in the labour market, as well as interests and desires;

- To be able to analyse the labour market by acquiring active job search tools;

- To design one’s own active employment seeking strategy;

- To be able to control and redesign one’s own strategy;

- To learn how to effectively utilize communication in active job-seeking activities by modulating timeframes, registers, language, decoding messages and analysing them critically in relation to various situations of job interviews, reading and replying to job adverts, writing a cover letter;

- To learn how to use all sources of information relating to active job search: newspapers, job search web sites, internet, yellow pages, word of mouth …;

- To learn how to assess information and judge it based on the goal.

This learning module too includes a well-defined path of activities. After introducing the goals and the type of work to be done together, the coach will help the young person (individually or in group) to work on the demand side and the tools. The starting point is certainly represented by writing, updating or perfecting one’s own CV: by working on this together, the young person is led to recognize and acquire awareness of skills, knowledge, abilities, but also personality traits, desires and motivations, expressed both at work and in life as a unity of self. At a later stage, the coach will help the young person prepare cover letters or motivational letters for each professional profile matching with the outcome of the list of skills. This step leads the young person to realistically recognize his/her own value in the labour market, interests and desires; at the same time, various professional profile types in addition to the pre-set ones can be identified and an application can be made based on one’s own competencies. Preparation for the job interview consolidates the awareness of competencies, knowledge and skills, as well as of personality traits. The coach can develop the ability of the young person to effectively make use of communication in active job search across these three activities by modulating timeframes, registers, language, decoding messages and critical analysis relating to various situations, from a job interview to writing motivational letters or replies to job adverts. Also, learning modules about new communication tools are on the rise such as creating a profile on LinkedIn or other national and international platforms (EURES).

The second step of the active employment seeking process concerns the job offer. Firstly, the young person is helped in how to set up his/her individualized active search by populating a personal digital database. This is made possible thanks to work on job offer analysis tools such as:

- setting up one’s own network and personal contacts;

- search for company web sites, job vacancy pages and submission of self-applications;

- registration with temporary employment agencies;

- search and reply to job adverts.

In the course of the learning module, the coach makes sure that personal responsibility is activated and progressing, for example by monitoring the database built by the young person and any enhancement and growth of search areas and tools.

3.3.3 Intermediary work with companies and employment counselling

The various activity modules related to active job search allow the young person to make the first contacts with companies, also through the EO’ intermediary work, which monitors job vacancies and directly points out applicants that have completed their educational pathway, thus taking on the responsibility to match job offers and the individual’s profile. Through this work, the EO makes the transition more effective and less risky to the young person and, at the same time, it engages often reluctant companies to take their chances and play a role in the process to employability of young people.

Employment counselling and matching of demand and supply by the EO makes a company more inclined to hire as it is aware that the newly-hired will be supported and coached during his/her first work experience. This service evidently helps not only the young person but the company itself that is relieved from operating costs related to introducing a new, young person, often with a tough background. In this phase the EO’s coaches pursue several goals that can be traced back to consolidating employability skills, such as growth-mindset, inclination to collaborate and proactivity. Topics discussed during meetings that take place during the first steps in a company include:

- learning how to know the work environment, the company, its characteristics, various professional profiles, manufacturing processes and intra-company communication methods;

- learning how to consciously act at the workplace, thus attaching meaning to one’s own action in relation to others and common good:

- awareness of the need for further training, learning a methodology to achieve excellence;

- recognition of one’s own limitations in growth areas ahead of long-life learning;

- learning relational skills, specifically in team work, problem-solving, conflict management and sharing of information.

3.3.4 Tutoring

The final step in the context of transition to employment is tutoring. This activity differs from previously described counselling as it is mostly designed to monitor the progress of the work pathway and facilitate the young person to learn how to recognize, express and assess emerging problems; together with the tutor it is possible to also identify solution strategies.

3.4 A peculiar form of transition: apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a form of work-based learning that is continuously growing in numbers, also following persistent encouragement by institutions, especially European ones, to increase its use. As a matter of fact, apprenticeship is a form of training where the dimension of transition to employment is concurrent and longer. For Cometa Formazione’s students that are on an apprenticeship program, the EO is directly involved in profiling the student (together with school tutors) and matching supply and demand with companies.

3.5 Education on management of school-work transition

Competencies acquired by the EO have recently allowed to deliver a proper training service for players that are interested in getting a better knowledge of Cometa Formazione’s method. The target also includes other training centres, youth employment providers or public agencies and institutions (both national and international); several requests are also submitted by tax lawyers or business consultants that are interested in getting a deeper understanding of the rules and tools of work-based learning or apprenticeship for their clients. During 2017 the EO organized several training courses both at Cometa and outside, at the headquarters of the relevant interested organization.

4. Development prospects and relations with the local community

As far as documented in the first steps of this research project, the EO’s activity is part of a social and economic context that is continuously evolving and rapidly growing. Progressive crystallization of tools, contents and practices would not be effective as it would lead to rapidly decreased efficiency. For this reason, the activities reported about in this paper are always steadily evolving, in line with the needs and occurrences arising from the confrontation with institutions, companies, and the recipient target.

Some of the next development guidelines have already been identified, first and foremost in favour of an increasingly higher degree of integration of activities completed during and after the vocational training program: next to the revision of the Internship TU, activities will be integrated to support also former students who are on extra-curricular internship programs and extended to active job search. In this respect, building, monitoring and offering services to the network of Alumni is certainly one of the most relevant short-term goals, thus favouring the occupational mapping process too. Growing attention has already been placed on employability and occupation of certified and disabled students: a model to support active job search for former students with special learning needs is being designed thanks to a more intense cooperation with the school’s team of special needs teaching assistants, which also covers the relationship with families.

Cooperation with companies remains a key factor: optimizing the supply and demand match should lead the EO to provide a reply to companies in as long as 5 working days max. At present time, this relationship is personally taken care of by an individual in charge of each of Cometa Formazione’s areas of interest. The area manager himself/herself is tasked with periodical visits to host companies, also with the aim to check the performance trend and evaluate the effectiveness of the work pathway or to promote a new one. These occasions proved to be crucial for different reasons. Firstly, for the manager of community relations, to collect the demand for professional skills required by companies and so allow the school to design its training offer based on real company needs or real professional opportunities; for companies and, specifically company tutors, who can be constantly supported in managing the educational relationship with the young person. Finally, for youngsters that are employed in a company and are, thus, supported in real time to manage any relational or organizational issues and to overcome fears, difficulty or distress.

Relations with the company are also enhanced by more or less informal meetings, such as conferences, dinners or lunches on school events like the final examinations for the dining room and bar specialist training program (consisting of preparing and providing service at dinner or lunch) or Cometa’s year-end party. The following picture sums up goals and occasions to get in touch.

Figure 7: flow of the company-EO relations

Internal source

5. Evaluation of the approach

Work carried out by the EO is constantly monitored through ongoing analysis of the employment rates for young people that have attended the program. Obviously, most recipients include students graduating from Cometa Formazione’s school, hence analysis relating to the employment rates cannot presently be traceable to the specific contribution provided by the EO vs. general education delivery. Results relating to outcome and social impact have been the focus of a research project from last year. New analysis is currently being carried out and the results will be made available at the end of 2017-2018 academic year.

The main purpose of monitoring is to identify the employment status of young people with qualifications and diploma obtained from Cometa Formazione or young people followed directly by the EO to promote their employability.

In turn, this first stage becomes an operating tool available to the EO to achieve 4 additional goals, still in support of youth and their employability after completion of the course of study. Specifically:

- to orient former unemployed/jobless students to enter a course of study (e.g. ITS/IFTS);

- to support former unemployed/jobless students to actively seek a job and make them independent in their search process;

- to match supply and demand based on job applications/extracurricular internships that the EO receives weekly;

- to put forward active regional policies.

5.1 Mapping methodology and tools

Data monitoring and collection includes 5 steps:

- STEP 1: extraction of master data from CRM relating to young people receiving counselling services in the past 6 months;

- STEP 2: phone interviews to collect mapping data;

- STEP 3: transfer of data collection to designated tools;

- STEP 4: data analysis and processing of final reports;

- STEP 5: definition of measures targeted at increasing employability of mapped-out youngsters.

In any case, the mapping process covers also young people that were followed in the previous 5 years, thus allowing the EO and Cometa Formazione to properly map not only recently trained students but also to assess their employability in the medium-long term and, if necessary, take action with new supportive measures.

Data collection is generally completed through a phone interview (up to 3 calls each time) made by school tutors that followed a certain set of students; in case of no reply, alternative options are utilized such as submitting a text to call back or verification through social networks.

Mapping includes data related to:

- Number of employed people (or on a tertiary course of study), including:

- areas of employment (woodworking, textile industry, food services);

- employment contract type;

- intermediary work by Cometa on integration in labour market.

- number of young people on extracurricular internship;

- number of unemployed.

In addition to this information, the phone call also investigates into the path followed by former students and their satisfaction.

Data collection (every 3 months) is transcribed to a specific form including the following items:

- Picture

- School year

- Demographic details

- With own car (yes/no)

- Curricular internships completed during study

- Remarks by the tutor indicating the characteristics of the student

- Latest update of the employment status

- Employment status

- Employment contract type

- Contract expiry date

- Area of integration in the labour market

- Intermediary work by Cometa

- Company where current working activity is performed

- Presence of CV in the VET centre’s database

- Job offers provided by VET centre

- Job offers accepted

Following the above-described mapping process for occupational outcomes, quarterly reports are then devised and shared with the leadership.

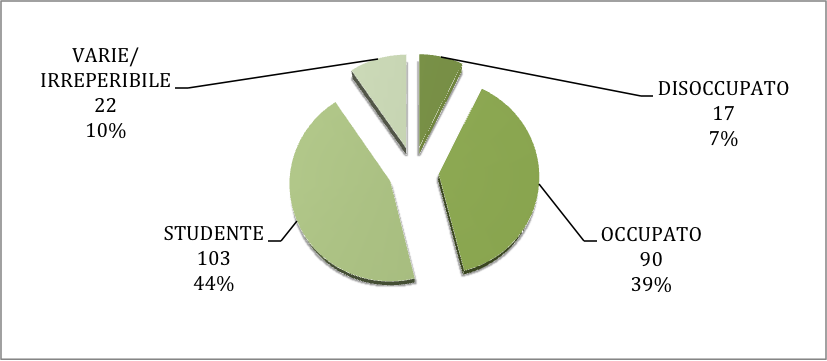

5.2 Placement data

Occupational mapping is completed annually, 6 months after graduation, even though 8-month data is turning out to be more solid. The latest mapping of students graduating in June 2017 confirms Cometa Formazione’s positive results in terms of educational and training activity as well as counselling to employment.

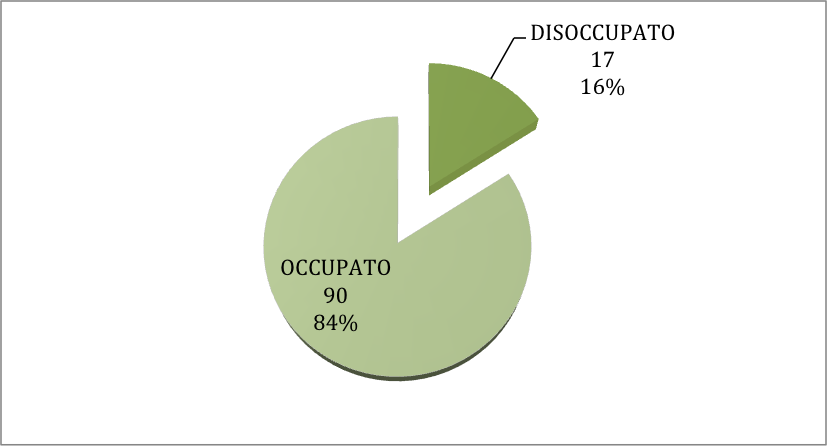

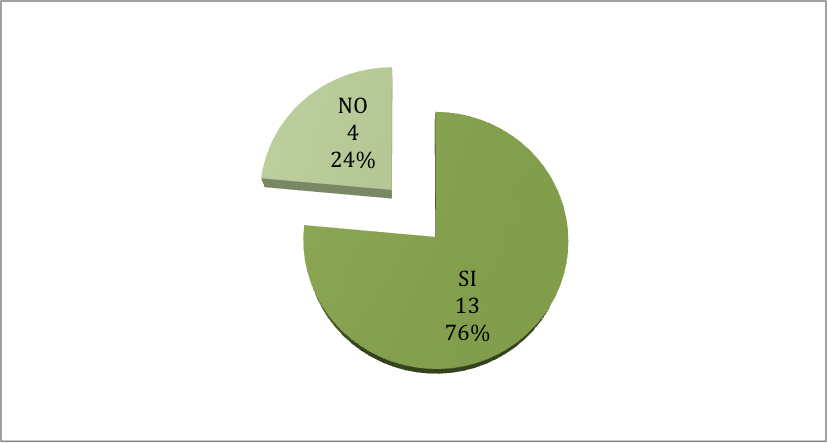

Following data collection, several indicators were developed as reported in the following charts.

Fig. 8: 2017 occupational results – mapping outcome

Fig. 9: 2017 occupational results – focus on employable individuals (excluding students and non-respondents)

Fig. 10: 2017 occupational results – presently unemployed who worked in the previous 6 months

Positive data also stands out from an analysis covering the past 3 years: 80% of young people followed by Cometa is on a course of study or has a job; employed people are stable in more than 60% of cases.

6. Emerging policy implications

A more stringent cooperation between education and the business world is at the heart of national and international debate today. Communications released by the European Union, reports by major international organizations such as the OECD and World Economic Forum demand tools and measures geared to this direction. Work performed by Cometa Formazione and the attached Employment Office in terms of preparing young people to transition from school to work and counselling them throughout this process is headed exactly in this direction. In fact, on the one hand, work is done with young people, on the other hand companies are involved and supported.

In this respect, fostering the accompaniment efforts to manage the transition is appropriate, especially with adequate financial resources, not only in terms of support but also building networks that bring together teachers, families, companies and institutions. Research itself is relevant to capture market needs that are continuously evolving, thus providing the opportunity to players like Cometa Formazione to constantly focus their outlook on the medium-long range and so offer a more effective employment counselling service as well as more stable employment results. The ability to anticipate market’s needs often demands an outlook that goes beyond domestic borders and the ability to read through current trends.

As part of the school-to-work transition framework, overcoming risk associated with invisible skills as mentioned in the beginning is of critical relevance. Helping companies to learn how to spot the necessary skills and capture them in the applicants, as well as supporting young people to recognize and communicate their skills are a major barrier to prevent growth of skill mismatch and, consequently, unemployment.

*“Go! Youngsters and employment, innovative careers in key sectors of the Como area” is a project implemented by Cometa Formazione from April to December 2018. A final conference was held last December 10th; documents are available here.

The intervention has been supported by the European Union within the framework of “Lombardia Plus 2018” program of POR FSE Lombardia 2014/2020 – Axis III – Action 10.4.1.: an initiative of Lombardia Region which supports training and work placement of unemployed or disadvantaged people in the key and growing sectors of the Region.

References

Alessandrini, G. (a cura di) (2017). Atlante di pedagogia del lavoro. Milano: FrancoAngeli

CEDEFOP (2015). Matching skills and jobs in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office. http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/8088

CEDEFOP (2018). Insights into skill shortages and skill mismatch: learning from Cedefop’s European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/645011

Dagnino, E. (2017) People Analytics: lavoro e tutele al tempo del management tramite big data. Labour & Law Issues, v. 3 (1), pp. 1-31.

Dato, D. (2017). Pedagogia critica per il futuro del lavoro. In: Alessandrini, G. (a cura di). Atlante di pedagogia del lavoro. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

European Commission (2016). Communication: A New Skills Agenda for Europe – Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness. Disponibile su http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15621&langId=en

European Parliament (2006). Raccomandazione 2006/962/CE del Parlamento europeo e del Consiglio, del 18 dicembre 2006, relativa a competenze chiave per l’apprendimento permanente. GU L.394 del 30.12.2006, pag. 10-18.

Fornasieri, F. (2017a). Educare alla creatività per affrontare le sfide della grande trasformazione del lavoro. Postato il 22 novembre 2017 su https://cometaresearch.org/educationvet-it-2/educare-alla-creativita-per-affrontare-le-sfide-della-grande-trasformazione-del-lavoro/?lang=it

Fornasieri, F. (2017b). Le conoscenze e competenze collegate allo sviluppo della creatività in ambito scolastico. Mimeo.

Fornasieri, F. (2018). Ripensare la didattica a partire dall’esperienza di stage: la potenza del compito di realtà. Postato il 21 marzo 2018 su https://cometaresearch.org/educationvet-it-2/ripensare-la-didattica-a-partire-dallesperienza-di-stage-la-potenza-del-compito-di-realta/?lang=it

Hall, D.T. (1976). Careers in organizations. Pacific Palisades: Goodyear.