Recent debate on VET, at both institutional and academic levels, points out the need for new approaches able to face the current and future challenges: (technical and social) innovation, attitude to lifelong learning, internationalization, literacy, among the others (Dato, 2017). A stronger partnership between the industrial and the educational systems is increasingly suggested (WEF, 2016). However, it is clear that rather than rooted only on work-based learning, the needed competences for the “unknown future” (Mulder, 2017) depend on new approaches able to stimulate in the students/apprentices a lifelong learning attitude (Pouliakas, 2017). This research, based on a case study analysis, aims at outlining the main elements of originality of a new approach called “reality-based learning” developed by Cometa Formazione-Oliver Twist School and measuring a set of KPIs to evaluate outcomes and social impacts of the approach. In this approach, both the professional training and the general education are integrated in a learning process based on involving students in the design and production of real products for real customers in school’s workshops. The analysis outlines mainly positive results in terms of human and relational growth; cultural and professional growth; school dropout reduction and public system savings; employment increase.

(Article by Paolo Nardi and, from Politecnico di Milano, Irene Bengo and Debora Caloni, presented at ECER 2018 and published on the Special Issue of IJRVET)

Introduction

Recent debate on Vocational Education and Training (VET), at both institutional and academic levels, points out the need for new approaches able to face the current and future challenges: (technical and social) innovation, attitude to lifelong learning, internationalization, literacy, among the others (Dato, 2017). A stronger partnership between the industrial and the educational systems is increasingly suggested (WEF, 2016).

To this extent, the great drive towards work-based systems (EC, 2016), including dual systems and job-school rotation, is based on acknowledging that workplaces can serve as an opportunity to perform work actions and typically educational measures. The workplace can be conceived as a cultural heritage that the school may make instrumental use of in favour of its educational goals, thus adequately combining training delivered in its premises with training measures completed at work. Research and study into these models, however, identify increasingly less interest in school subject-matters, with a growing risk of a gap in literacy and numeracy, in addition to a perception of mere juxtaposition between so-called theoretical and professionalizing subject-matters, at the expense of the former in terms of commitment.

Such risks first of all take the shape of a mismatch between contents developed in school and those arising from the labour market (Aakernes, 2016), which is often the result of a missing dialogue between school and companies and lack of a serious and consistent analysis of market needs (Hiim, 2015). Therefore, students feel that learning through curriculum subject-matters is boring (Hagen e Streitlien, 2015) and useless (Rintala et al., 2016); sometimes, also due to lack of time for an individualized study process, curriculum subject-matters are considered less relevant with respect to pursuing work targets set by companies and as such they are neglected.

Furthermore, cultural difference, both in context and experience, leads school and company stakeholders to different views, which is not instrumental to a successful training (Aakernes, 2016; Andersson et al., 2015; Billett, 2011; Young, 2004). In this respect, it may be useful to promote more regular convergence efforts by school entities (tutors and teachers) and company entities so as to agree on goals but also on criteria to evaluate training and competences.

Henceforth, it is clear that rather than rooted only on work-based learning, the needed competences for the “unknown future” (Mulder, 2017) depend on new approaches able to stimulate in the students/apprentices a lifelong learning attitude (Pouliakas, 2017). A system where developing students’ capabilities (Nussbaum, 2011) becomes the main goal of teaching and training activities: future workers need not only professional skills for a (less and less) permanent job, rather they have to develop personal capabilities to keep themselves employable and smart citizens, the only way to safeguard social cohesion in the next decades (Nussbaum 2010). In a nutshell, school should not be required anymore to give only information: education implies to be able to inquiry reality, to catch the meaning and the beauty of it, but, above all, to make the right questions; henceforth, to support students to a deep self-knowledge, pointing out their capabilities and their potential “excellence” as human being (Nussbaum, 2011).

This research, based on a case study analysis, aims at (1) outlining the educational and training practices which denote the main elements of originality of a new approach called “reality-based learning”; (2) identifying the key players and their roles in the educational process; and (3) implementing and measuring a set of KPIs to evaluate outcomes and social impacts of the approach.

Methods

The research is based on Cometa Formazione-Oliver Twist School case study and its reality-based learning approach.

Cometa Formazione-Oliver Twist School is an educational organization specialized in vocational training and job orientation that has been operating in the province of Como (Italy) and its surroundings for a decade. Cometa started as a training center focused on NEETs. This educational challenge required the introduction of innovative learning approaches which are now at the core of the VET school “Oliver Twist”. Its offer includes:

- TVET programs for 14-19 y.o. kids in 3 different tracks: catering, carpentry and fashion.

- Special programs for dropouts (Liceo del Lavoro): 1 or 2-years programs based on a dual system approach.

- Special programs for NEETs (MiniMaster Alberghiero): 1 year program or training modules for NEETs focused on a strong work-based experience in the hospitality sector.

- Training program for migrants, mainly unaccompanied minors, including basic literacy, numeracy, digital and an internship.

Overall, Cometa Formazione hosts more almost 450 students; the teaching staff consists of 41 teachers (including 9 master craftsmen), 7 co-teachers and the principal for a total of 49 professionals, with an average age of 40 years and a balanced gender division; tutoring is carried out by 14 professionals (including deputy principal and 4 area coordinators), with an average age of 35 and a prevailing presence of women (82%). Taking into account membership and distribution of staff (teachers, special needs educational assistants and tutors), the ratio between kids and adults is approximately equal to 6 to 1.

Results

Originality of Cometa Formazione-Oliver Twist School approach

In line with well-known approaches – learning by doing (Dewey, 1916), experiential learning (Kolb, 1984), and action learning (Marquardt & Yeo, 2012) – Cometa Formazione-Oliver Twist School, has implemented the reality-based learning approach. Both the professional training and the general education are integrated in a learning process based on involving students in the design and production of real products for real customers in school’s workshops. Thus, the whole learning process, including all the mandatory professional, basic, cultural and human skills in the educational curricula, has been designed accordingly to a production process. Henceforth, the emerging result consists of a hybrid of school and workplaces (Cremers et al. 2017), a laboratorium where “theoretical thinking” has to be in connection with “technical making” and practice, with the same dignity (Gardner, 1983).

This approach, to some extent, rethinks the Italian tradition of medieval workshops or the Renaissance studios, as well as the countless small artisanal micro- or small enterprises promoting the Made in Italy and the Italian way of life worldwide. It aims at giving an example of a context where education and training are both present, but not merely focused on professional skills. In the Middle Age, the craftsman assumed a parental role to trainees in the workshop, making them adults not just workers. Sennett, in his work “The Craftsman”, underlines the relationship between «hand and head, technique and science, art and craft»; the workshop (then a “workshop-home”) becomes a centre of culture; craftsmanship, according to Sennett, can be intended as “an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake” (2008). It is one of the best examples of experiential learning represented by the concept of homo faber: an experience shared by Ancient Greece, China, Medieval and Renaissance Europe. In the laboratorium “theoretical thinking” has to be in connection with “technical making” and practice; they mix together in the action, with the same dignity (Gardner, 1983).

There are 3 workshops-enterprises (called “bottega”) in Cometa, namely: Bottega del gusto (Taste), including a bar, a restaurant and a pastry shop open to the public; Bottega del legno (Wood), including a planning and design dept. plus a carpenter’s workshop; Bottega del tessile (Textiles), including a design dept. and a textile shop (mainly fabric).

The reality-based learning approach is based on project works and on educational units. Starting from the abilities that need to be obtained by every single pupil, teachers design educational paths, which accompany students during their project realization. Students unroll typical work activities in order to acquire basic, transversal and technical-professional competences. The educational tasks of the working environment are planned not in a practiced manner, but following a holistic approach: students are introduced to the entire production chain to gain a complete vision, but also to discover their talents and preferences.

Furthermore, during the entire learning process skills are transmitted to the students. These abilities are divided into two big sections: (a) professional/ technical competences and (b) basic skills, such as abilities referring to the administration of the product and the process (languages, history, public speaking, etc.), and promotional skills (mathematics, science, economy, etc.). Soft skills are needed in every single moment during the learning process.

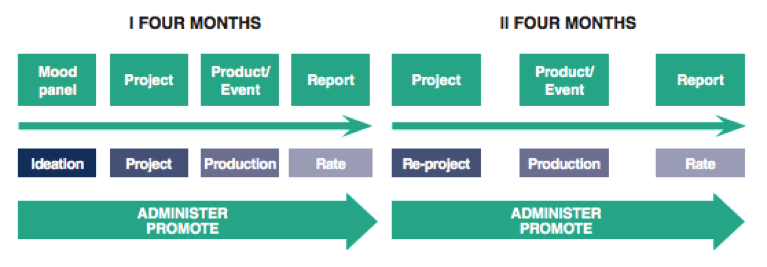

The educational model of Cometa Formazione divides the learning process in four different phases: 1. Ideation, 2. Project, 3. Production and 4. Rate, as in the figure below.

At the end of every section a product is being created: (a) a mood panel, (b) a project or prototype, (c) a product or event and (d) a report. The whole process is repeated twice a year. It is not a rigid model, but it depends on various factors, such as the class and the projects. Moreover, this learning process can be adapted to different sectors.

The scholastic year starts with the process of ideation, during which different activities are planned to understand the object’s context as much as possible. Therefore, these activities are planned also to help students being aware of where they are and of what Cometa means. Every product created in the Oliver Twist school has the Cometa brand.

Ideation plays a very important role of Cometa Formazione’s entrepreneurship education. Giving students the possibility to work on the ideation of a product and on their creativity represents an extraordinary opportunity. During this phase it is very useful to work on the student and on its subjectivity and protagonism. It is important to let students know that their opinions count and contribute in an original manner to the common construction. It is about active citizenship. Most of the time pupils do not believe in themselves and do not consider themselves as important. Therefore, it is necessary to show them that they give value to the group.

The second phase regards the process of project, which first of all corrects what was ideated during the first phase. The educator interferes thanks to his experience and helps the students in evaluating if their ideas are realizable in terms of costs, materials, market etc. Moreover, this phase is not only based on technical terms but also on the way of being. Therefore, the companies transmit technical knowledge and abilities, whereas, the school has the task to teach men and women the right way of knowing how to get by in this world. Again, it is necessary to understand the best way to respond to the client’s needs on behalf of Cometa.

The third phase is about production, that foresees manufacturing of the prototype chosen by the client. In this way, it is possible to present a realistic scale model during the following meeting. In case the client is satisfied with the prototype, students start realizing the products. Its duration depends on the specific work field. Shortly, it is the examination of the previous phase: if everything went as it was planned, the realization can be unrolled without problems; if not, the realization must be modified until the predicted results can be really produced.

The last phase regards the rating, during which the whole educational process is evaluated. This phase is fundamental for having a judgment and measure of the educational path and its outputs. The complex of systematic and continuous observation carried out by teachers guarantees a tool for evaluating the formative programs.

Evaluation allows teachers and students to reflect on the model and the process in order to develop possible critical issues. Furthermore, the evaluation of competences acquired in the working context takes place through constant monitoring and by analyzing the company’s feedback.

During the whole process the relationship student-tutor is crucial. The tutor is the one that makes the communication between student and teacher smoother, in particular outlining students’ learning needs and personal situations. The tutor is present during the whole learning process and helps the students organizing their educational program, adding for example more study hours in order to guarantee a better assimilation if needed. They are also in charge of planning and monitoring students’ internship: ever since their second year, students make also an important internship experience in local companies for an overall period of 2 months a year.

Throughout the entire internship, the pupil is supported by the school tutor who will periodically visit the host company. The focus of such visits is to establish a direct contact with the pupil and the company tutor, but also to conduct separate meetings with one of the two individuals for monitoring purposes and also to identify any issues that may arise during the internship period. The internship experience may be divided into three phases: planning, work experience, evaluation.

- Planning: a company is selected for each pupil based on a set of criteria shared with all the players: school management, tutor, company manager and teachers.

- Work experience: from the start date and throughout the internship provision phase, the tutor is in charge of monitoring the job-school rotation program to confirm the educational value of the internship and of the educational support care. This educational support care implies a multitude of activities aimed at leading the student to make an experience that is truly educational and delivering both professional and human growth. The most relevant is the choice to have pupils back in classroom once a week for a day to allow them to incorporate the experience in the company; the tutor is responsible for arranging such day.

- Evaluation: the school tutor will draw up the internship satisfaction questionnaire for the company and the pupil, check and store the attendance logbook of each student and arrange for individual interviews with pupils and business tutors. The interview with the business tutor shall specifically try to explore any possibility for a potential future job of the pupil in the company, whereas the interview with the student allows to formulate a summary report about the experience and to prompt continuous commitment at school.

Beside the relevance of the organizational elements of any job experience during IVET, at the very core of this activity, both the quality and the commitment of actors play a crucial role: excellent trainees require the support of excellent trainers to make their job experience successful. Timing and location have only a secondary importance. Furthermore, the relevance of their educational support can only be rooted on a business-education partnership aiming at realizing a “tailor-made” project for each student. Unprepared internships, for instance, can be highly unsuccessful, while an effective learning agreement usually implies a deep and regular partnership between the company (tutor) and the school (tutor). A real educational pact, among company, school and each student, is the key issue (Ropelato, 2017).

Outcomes and social impacts of the approach

The success of the reality-based learning approach has been evaluated through a quali-quantitative analysis of outcomes respect the primary beneficiaries (students) and the impact on the local community.

The analysis outlines mainly positive results in terms of human and relational growth; cultural and professional growth; school dropout reduction and public system savings; employment increase. In particular:

- human and relational growth: 95% of students recognize their soft skills increased, more than 75% of students believes that they have been helped to accept the others and the diversities and more than 80% of students admit their relations are improved.

Some of them declared: “Working in group with peers, adults and people with disabilities helped me to accept all people”; “I had the opportunity to meet and work with people external to school”; “I was helped to face difficulties”; “I had the possibility to discuss and share opinions”;

- cultural and professional growth: 93% of students believe they have been grown professionally.

Some of them declared: “The work activities at school allowed me to acquire the useful professional knowledge because I was obliged to do my best, understanding my strengths and weaknesses”; “The “learning by doing” approach is very effective because while you are doing something and you do not understand it, you can immediately ask and better understand it. So, while you learn the practice, you can also learn the theory”; “In my opinion, the most interesting activity is the orders management, where you have to collaborate with peers and improve your skills”; “I worked in front of real customers and I learnt from mistakes”.

- school dropout reduction and public system savings: every year Cometa trains about 50 students who had left school. 90% of them had completed their new career at Cometa. These students generate about 650.000€ public savings per year.

- employment increases: so far, since 2012, more than 60% of former students got a stable employment and are no longer completely dependent on their families (the average salary is 900€/month); 70% of employed students work in the same field of the educational path carried out; the employment rate of graduates is 8% higher than other VET schools in Italy.

Conclusion

The research led to the outline of the reality-based learning approach, pointing out the process, its phases, activities, key players. Innovations in the training process have been described and explained in connection to the pursued educational goals: basic, professional and soft skills.

Beside the professional identity of the students, future-oriented competencies (Mulder, 2017), relevant for learning motivation, effective performance, social inclusion, and citizenship, are taken into great consideration; tutors (acting more as coaches) play a crucial role not only at the more personal level of the students, but also in the general coordination of the learning/production process for every class and their teachers.

There is an evident effort to overcome the division into subject-matters and disciplines in the same course of studies as well as the historical dichotomy between doing and knowing, theory and practice, vocational-technical subject matters and “basic” ones. Started since 2011, this new teaching methodology has been developed to make experience as the pivot for learning and developing different skills, including non-technical ones that activated in the making or rendering of a product/service. In addition to soft skills, also competency in mathematics and languages are required to deliver a final product of excellence.

Such teaching structure is underpinning the reality-based learning, whereby an order received by the students represents the point of engagement and the source of endless learning opportunities for new skills and not just new knowledge. In this way, the entire teaching methodology is not only an interdisciplinary one but actually pervades multiple disciplines: a student in action is demanded to put in practice skills of different nature, which ultimately leads the students to overcome division of knowledge in the making of their masterpiece and to favor a holistic approach. To such end, it is necessary to establish a more solid relationship between places and moments for learning and places and moments for application of the learnings. Working actions and typically educational measures can be taken also in workplaces. In fact, the workplace is to be intended as a cultural resource field that the school can utilize as an educational means, thus adequately combining training actions performed at school and in the selected workplaces. To this purpose, criteria and operational methods are needed to analyse working processes and to locate knowledge and skills required by national regulations for secondary school programs and vocational training programs.

In line with recent EU documents claiming for “making VET a first choice”, this reality-based learning approach and its implementation show positive results in terms of effectiveness, quality of outcomes and relevance of the generated social impact. Positive results emerge also for special categories of young people including dropouts, potentially dropouts, youngsters of underprivileged groups.

Further developments of the research can already be mentioned as potential improvements, namely the following: (1) comparing the results of similar approaches in other contexts to strengthen the effects of reality-based approach (2) introducing counterfactual analysis for a stronger significance of the impact analysis.

References

– Aakernes, N. (2016). Coherence between learning in school and workplaces for apprentices in the Media industry in Norway. Paper presented at ECER 2016.

– Andersson, I., Wärvik, G.-B. & Thång, P.-O. (2015). Formation of apprenticeships in the Swedish education system: Different stakeholder perspectives. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training (IJRVET), 2 (1), pp. 1-23.

– Billett, S. (2011). Vocational Education: Purposes, Traditions and Prospects. Dordrecht: Springer.

– Cremers, P., Wals, A.E.J., Renate, W., & Mulder, M. (2017). Utilization of design principles for hybrid learning configurations by interprofessional design teams, Instructional Science. 45(2), pp. 289–309.

– Dato, D. (2017). Pedagogia critica per il futuro del lavoro. In: Alessandrini, G. (Ed.). Atlante di pedagogia del lavoro. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

– Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan.

– European Commission (2016). Communication: A New Skills Agenda for Europe. Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15621&langId=en [last access: July 4th 2018]

– Gardner, H. (1983), Formae Mentis. Saggio sulla pluralità dell’intelligenza, Feltrinelli, Milan.

– Hagen, A. e Streitlien, Å. (2015). From talent to skilled worker. Telemark University College: Final report.

– Hiim, H. (2015). Educational Action Research and the Development of Professional Teacher Knowledge. In Gunnarsson, E., Hansen, H. P., Nielsen, B. S. (Eds.). Action Research for Democracy. London: Routledge.

– Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

– Marquardt, M.J., Yeo R. (2012). Breakthrough Problem Solving with Action Learning: Concepts and Cases. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

– Mulder. M. (Ed.) (2017). Competence-Based Vocational and Professional Education. Bridging the Worlds of Work and Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

– Nussbaum, M.C. (2010). Not for profit: why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

– Nussbaum, M.C. (2011). Creating Capabilities. The Human Development Approach. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

– Pouliakas, K. (2017). Strengthening feedback between labour market signalis and vocational education and training. In: Alessandrini, G. (Ed.). Atlante di pedagogia del lavoro. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

– Rintala, H., Nokelainen, P. & Pylväs, L. (2015). Katsaus oppisopimuskoulutukseen: institutionaalinen näkökulma Review of apprenticeship education and training: an institutional perspective. Paper presented at ECER 2016.

– Ropelato, R. (2017). From Job- to Career-Training: Tools for a Growth Mindset in VET. Paper presented at ECER 2017.

– Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

– Young, M. (2004). Conceptualizing vocational knowledge: Some theoretical considerations. In Rainbird, H., Fuller A. & Munro A. (Eds.), Workplace learning in context. London: Routledge.

– World Economic Forum (2016). Future of Jobs. Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Available at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf [last access: July 4th 2018]