This document intends to explore any possible connection between Team Building efforts, training of teachers along an educational pathway and experiential learning. Team Building is increasingly valued in the business community as an activity which turns a group of people working together into a team. Through the analysis of some theoretical concepts behind such practice, the intent of this paper is to identify and lay the foundations for the development of the same process in a school setting, from the viewpoint of training the teachers.

Afterwards, through the proposition of a fractal model, the author will analyze how this can deliver a positive impact on the learning level, both from a standpoint of strategy as well as outcomes.

1. Introduction

Is there a possibility to improve collegiality in the Italian school system? This paper intends to address this question, already raised by Anna Marra in 2009 1 , to try and identify its key points and to provide an answer in light of the findings from field research.

The current setup of Italian school institutes originated back in the year 2000 when the law on school autonomy came into effect. Such law was intended, amongst other innovations, to introduce an increased level of adaptation and flexibility in school settings, thus allowing for a slicker and more effective response to the needs of individual students which impact on coordination and management bodies of education providers, public and officially recognized ones alike, through the involvement of the teaching staff.

Another turning point in the way how the school world is to be conceived was the education system reform promoted by Minister of Education Fioroni, on August 22nd 2007 which introduced the “competence-based” teaching system.

Although this paper does not intend to dwell on the concept of Competence, already extensively addressed in the last few years both by Italian and international experts2, the author only recalls that such innovation meant to deliver school from an overall notions-centered approach, bound to the concept of a “syllabus”, in favor of a wider concept of learning, one that would outgrow the subdivision of subject-matters in pieces of knowledge and learning, and thus promote a path revolving around development and building of competences, as intricate as they can be by definition. Faced with such context, a lesson planning strategy that intrinsically goes across all subjects by the teaching staff turns out to be even more indespensable, with all its implications concerning not only the proposition to the students but first and foremost the concept of collegiality and sharing of goals.

2. Issues of the school as an organization

In light of the above-mentioned desirable changes, the Italian school landscape presents us with a remarkable limitation to implementing the concept of collegiality of teachers within the school organization3. As a matter of fact, the opportunities for a true exchange amongst teachers are limited in number and occasional as of today. Aside from class committee meetings that are usually focused on how individual pupils perform in various subject matters, there are rare opportunities for collegial lesson planning and designing where a learning path that applies across subject matters is unanimously developed.

Marra (A. Marra 2009) too points out the same issue:

«In his/her day-to-day work, each teacher always gets organized when he/he has to teach a lesson or tackle a specific activity together with his/her pupils» and then immediately counters such statement with the following: «Teachers, in fact, struggle to accept the collective dimension of work organization, because they don’t consider working together necessary». We believe the author has identified the pain point of school as a system in the (internal) organizational ability of the every player to come up with a teaching proposition that cannot be fully cohesive and orchestrated, unless some changes become real in the immediate future.Piero Romei also raised the same issue back in 19994. According to the author, the only way for the teaching staff to possibly take over an organic task is the creation of a “system of inconsistencies”, that is to say the ability to identify some balance, though uncertain, between

«Inconsistencies arising out of individual freedom» and «Behavioural guidelines needed to manage the system».

In the opinion of the two referenced authors, a successful introduction of an effective cooperative model in the Italian school system appears to be impossible, at least until the organizational structure itself changes in a more or less desirable future.

Marra (A. Marra 2009) even declares that collegiality is truly a «cultural accomplishment», which is only made possible through the application of «continuous and systematic practice». But then, how should a similar practice be proposed and how can it be effective and applicable to the Italian school?

3. Research questions and methodology

Lack of coordination for a shared objective in one’s own specific teaching practice stands out as a fact and as a gap to be bridged in the system under scrutiny. None of the two above referenced authors is able to deliver a suggestion on how to overcome such difficulty and define a model of collegiality that adequately caters to the identified needs.

Faced with such situation, the first research question emerges: is Collegiality of the Teaching Staff a real possibility and opportunity for the school? If that is the case, what kind of strategies could be put in place to achieve such goal?

And then again, could Team Building-related practices in their Outdoor variable represent a valuable answer to those needs?

This research tried to develop both a qualitative and quantitative survey.

First of all, a short nameless questionnaire was devised and administered to quite a small and yet heterogeneous sample of teachers with different backgrounds, seniority levels, practicing in different types of school institutes and teaching different subject-matters. Data from the questionnaires was then analyzed and represented graphically so as to provide a synoptic view.

Lastly, the set of activities developed as part of Team Building practices was taken into consideration and, our attention was specifically focused on Outdoor subject-matters because of their peculiarities.

With respect to the latter, a qualitative analysis of an initiative run during an in-house training Camp for teachers at Cometa Formazione scs is hereto presented. Activities submitted to the attention of the group will also be outlined, thus highlighting those aimed at improving collegiality.

The intent is therefore to present data from surveys and activities completed as well as to try and highlight possibile inputs for future work, which may lead to optimize the development of the model proposition, in addition to identify details of the most effective modes of action.

4. Teamwork in school: an analysis of italian teachers’ needs

The first step was to determine to what extent the need for collegiality intended as teamwork actually matches the wishes of teachers.

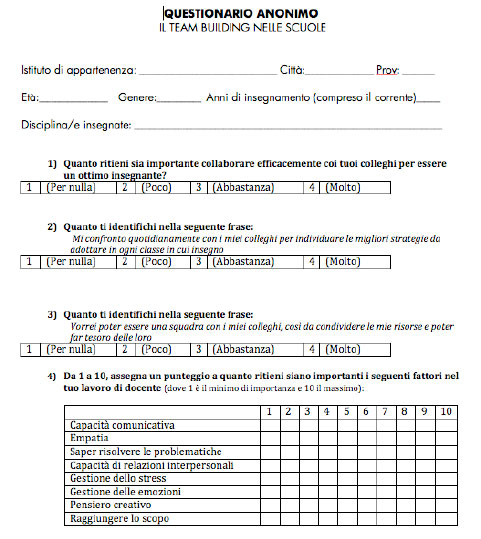

As already mentioned, the following questionnaire has been developed and is hereto attached, to complete this part of the job.

As you may notice, the questionnaire is organized around three simple key questions plus a question including eight different items; personal data collection is also included in the attempt to trace the age range of teachers involved, the school institute they teach at and their teaching seniority. In fact, this allows to include results from players that differ from one another by each of the above-mentioned criteria, thus resulting in a heterogeneous data collection.

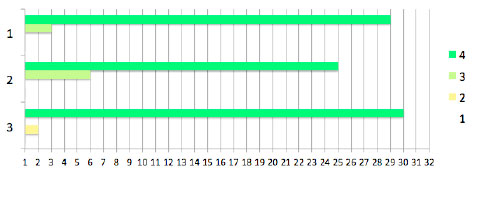

The scrutiny of returned questionnaires resulted in the following graph which provides an overview of data concerning the relationship between teaching staff and teamwork, as derived from the answers to the top three questions of the administered form.

The horizontal axis of the graph displays the number of interviewed teachers (32), whereas the question number in the questionnaire is shown on the vertical axis. Colours indicate the answers provided by the interviewees, which point out the extreme relevance generally attached to teamwork within school.

During the preliminary phase, this allowed to appreciate that the desire for teamwork is actually felt by teachers in the Italian school and to identify the need this research tries to cater to with a very first input for an answer. On the one hand, therefore, a strong need is felt in this respect, whilst, on the other hand, the question as to how collaborative actions may be implemented is still pending. Whilst almost all interviewees state they have daily exchanges with their colleagues (as indicated by answers to question no. 2), figuring out how such aspect can be addressed in a systematic manner still appears to be difficult, especially in consideration of the hourly workload distribution per teacher and the fact that they don’t stay at their workplace longer than the lesson timetable requires.

It is believed that an exchange does take place daily, but thanks to the individual teacher’s initiative and only on an informal basis, during the “time gaps” between classes, without any character of systematic consistency. Therefore, a collegiality model that is effective, efficient and optimized is still far.

Question number four, instead, intended to explore another aspect of our research, namely in relation to a possible strategy to improve the attitude to collaborate.

The eight items listed in this question, in fact, were not chosen by chance; various authors 5 indicated them as easy to be implemented through Team Building activities.

Experts in this area have always looked at these qualities in light of improving teamwork in a company, without really taking into consideration the Teaching Staff as a set of professionals that are also expected to closely collaborate to achieve a common goal, that is to say successful learning for each pupil.

Although this perspective does pave the road for other remarks, such as centredness of the pupil as a person in the school system 6, we’d like to focus the attention of this research on qualities required of the business community and then developed through Team Building and ultimately understand whether the same qualities are actually seen as important by teachers in the Italian schooling system.

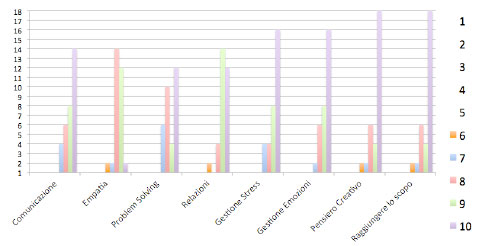

The following graph displays scores assigned to each item listed in question number four of the questionnaire on a scale from 1 to 10.

As you may notice, none of the eight items rated by the teachers was assigned a negative score, and only four items (namely empathy, management of relationships, creative thinking and accomplishment of goals) received a score of sufficiency in 2 cases out of 32.

Based on such results, it can be asserted that individual teachers indeed consider competences deployed through Team Building initiatives important to improve their professional performance.

Lastly, Italian teachers do wish to work as a team and improve chances of cooperation with their colleagues, they consider teamwork-specific qualities important but, as a matter of fact, the organizational setup of the Italian school does not indeed offer specifically-designated moments for collaboration amongst teachers, especially across various disciplines7.

5. Team Building as a possible answer

The previous paragraph has outlined the need by teachers in schools to collaborate as a team, as derived from data analysis.

Moreover, consistency between qualities considered important by the business community and the teachers’ community has also been pointed out.

Going back to Marco Rotondi (Rotondi 2004), we may state that any Team Building activity, whatever the context, will draw its preconditions for implementation from the area of experiential learning.

In the referenced publication, through a short overview of history and literature references, the author shows how the most important theorists of education for adults in XX century, both with American and European background, propose a learning model that is based on experience.

A quote by Rotondi himself summarizes the concept:

«There is no learning but with an anchor to real life»

Hence, on the one hand, experiential learning is the par excellence paradigm for personal growth in a group of cooperating individuals.

On the other hand, those activities geared to improve the work of a group, will provide an more solid answer to the teachers’ needs, as they emerged from our survey.

In order to clarify the relationship between collegiality and work, the model of a sports ground can be taken into consideration as a metaphore for the team, as indicated by Quaglino and Cortese (Quaglino-Cortese 2003) and illustrated below.

Team Building activities are aimed at sharing the four elements of the above graph: objective, resources, coordination and methodology.

By combining these goals with an experiential learning process, it is possible to outline some activities that may result in improved collegiality amongst teachers, that is the purpose of this research.

Around the end of XX Century some experiential learning methodologies became available, all of them originated in a business environment, mostly Anglo-Saxon and, specifically, US.

Europa was able to take ownership of such practices at the beginning of XXI Century, and Rotondi (Rotondi 2004) organized them in five groups differing by dynamics and implemented strategies:

- Self-training

- Learning Community

- Work Place Learning

- Coaching

- Outdoor Training

We would like to focus our attention only on the last group of these five, as it reflects research activity put in place as part of our field study.

Whilst the first four methods of «incisive education» (Rotondi 2004) are somehow traceable within the ordinary experience of a teacher in an Italian school, the last method requires a specifically designated time and place, in addition to a competent trainer that is able to lead the experience.

In the attempt to provide a definition of Outdoor training, we may rely on the definition by Rotondi:

«These are educational paths within a natural setting whereby participants meet outside of rigid and consolidated roles and organizational contexts and go through emotionally-engaging learning experiences, thus dealing with new and often unforeseeable tasks and situations, thinking about what has happened and therefore developing target skills and the ability to learn from experience» (Rotondi 2004).

As the author rightly points out, the last method is indeed the only one out of five that tries to combine different spheres of learning. As a matter of fact, although physical exercise only has a secondary relevance, it will involve the body of the participating individual but also the sphere of emotions. Outdoor Training can therefore be defined as a paradigm for holistic learning, easily applicable to daily working environments, provided it is properly led by the trainer in the debriefing8 phase.

6. Case study: cometa camp 2015

The second part of our research intended to explore the effectiveness of outdoor training in the field, namely within a school system, with the aim to enact a protocol for action and management of school activities previously agreed-upon during ordinary classes through experience. In order to improve learning as well as the ability to put in practice conceptual propositions through real experience, a full day of outdoor training was proposed. This outdoor training took place on July 3, 2015 in an outdoor field, properly equipped for the planned activities and was attended by 24 employees of Cometa Formazione including teachers, tutors and special education teachers. Please note that the multifarious character of staff involved in such initiative was a valuable asset with regard to the preset goals; if better cooperation and collegiality amongst different players in education can flourish, positive outcomes may as well be accomplished when such training methodology is addressed only to the Teaching Staff, in case some school institute only have this feature.

6.1 First part: Briefing

The training day opened with a short briefing to introduce the agenda and the preset goal, whereby a summary of work carried out in the class about sharing a common protocol for all colleagues was given; the participants were then subdivided into two groups, each supervised by a designated instructor. For this part of the day, subdivision into two groups was merely instrumental to a better management of planned activities, without introducing any competitive element.

6.2 Second part: propaedeutic activities

In order to create both emotional and psycho-physical awakening and connection, each group was led by the relevant instructor to complete a selection of activities aimed at prompting the body to respond to unusual situations, with a remarkable emotional prompt factor caused by some tests that purposely touched upon inner aspects that everyday life only deals with marginally. The proposition included, for example, completion of dynamic tree trails of various kinds to regain awareness of one’s own body structure, as well as situations where most commonly-widespread fears (achluophobia, acrophobia, claustrophobia) were tested and mastered, thus gaining more self-confidence in one’s own potentiality. As you may imagine, physical and emotional aspects were extensively prompted in this first part of the day, thus enabling the individuals to develop an increased self-awareness within a certain action.

6.3 Third part: communication, leadership and trust

After a lunch break where participants were purposely left free to intermingle as they liked, the two groups were further subdivided into two other sections. The resulting four crews were then given 30 seconds of time to independently choose a leader that would guide them through a forest that no other group member had previously explored. All the individuals, except for the leader, were blindfolded and they were required to pick up small objects scattered throughout the path following only verbal instructions given by the leader. You can easily imagine how, through this simple activity, the three factors (communication, leadership, trust) were stimulated and acted upon in a different way by each crew.

6.4 Fourth part: collaborating according to a preset method (protocol)

Two working groups were restored by pairing the four crews of the former activity. Each group was assigned a specific product (in this case a shelter) with some preset characteristics to be built within a precise timeframe (1 hour) using initially declared resources (materials collected in the forest).

Each team had to abide by a previously shared protocol, whereby tasks and responsibilities were assigned as well as the product creation phases: ideation, design, implementation and evaluation. Upon expiration of the available time slot, excellent results were accomplished. In this case too, communication and the choice of the leading characters for the various processing stages were found to play a predominant role for the success of the activity. In terms of qualitative analysis, the most important thing was that none of the teams asked the instructors (acting as a jury) which team had won: we believe this is the greatest result, because each team proved happy with their work and accomplished their goal by adequately collaborating with one another and comparison with the other team came to be of secondary importance against their own accomplishment.

6.5 Fifth part: final debriefing

After completing the self-assessment of their own work, the two teams gathered for a short final debriefing under the guidance of the instructor. All the factors covered by the protocol that opened the day did actually come across and translated in a real experience through tangible examples experienced in person by the participants.

Aside from the good memories of the day, the days following the training camp and spent in the classroom and no longer outdoor proved how valuable and effective the actions to improve collaboration and collegiality amongst teachers at Cometa Formazione were.

7. Future research developments

This document was intended to introduce a first study on the relationship between collegiality in a school context and outdoor experiential training activities, without certainly expecting to cover the questions raised in paragraph three.

A new outdoor training session has already been planned and it will involve more than 30 teachers at Cometa Formazione scs, only some of whom had the opportunity to attend the 2015 experience.

On such an occasion, our research will be extended to cover identification and measurement of the preset outcomes not only at qualitative level, but also in terms of collection of personal details, through pondered-out interviews and previously developed questionnaires.

Secondly, the plan is to promote administration of the questionnaire initially filled by 32 teachers as initial input for our study. The questionnaire will be disseminated internationally too, so as to complete an analysis across different countries and, above all, to verify if the profession of teachers in Italy is perceived in a similar manner also in other contexts which may differ by culture and structure of educational organizations.

As a final point for future developments, we plan to investigate how the practice of outdoor training for the teaching staff may have an impact on the students and its characteristics.

Which consequences can an improvement of the items cited by Quaglino and Cortese (Quaglino-Cortese 2003) have on the performance trend of the class as a group in terms of collaboration, development of skills and definition of a teaching method across different subject-matters that is based on experiential learning?

References

- Bertagna, Dietro a una riforma. Quadri e problemi pedagogici dalla riforma Moratti al «cacciavite» di Fioroni, Rubettino, Catanzaro, 2009.

- Lazzari, Il manuale del teambuilder. Tutto ciò che è necessario sapere per trasformare un gruppo di lavoro in una squadra e una squadra in una squadra specializzata, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2012.

- Morin, La testa ben fatta. Riforma dell’insegnamento e riforma del pensiero, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milano, 2000.

- P. Quaglino – Claudio G. Cortese, Gioco di squadra. Come un gruppo di lavoro può diventare una squadra eccellente, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milano, 2003.

- Romei, Guarire dal mal di scuola. Motivazione e costruzione di senso nella scuola dell’autonomia, La nuova Italia, Milano, 1999.

- Rotondi, Formazione Outdoor: apprendere dall’esperienza. Teorie, modelli, tecniche, best practices, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2004.