Debate clubs are the offspring of historical eighteen century London Debating Societies. Nowadays, debating is perceived as one of the most interesting and effective methods of teaching pupils and students entrepreneurial skills. Although there are many ways of debating, the most popular is the British Parliamentary Style (BPS). According to BPS, there are two counteracting parties which argue around the given topic and try to persuade the adjudicators and the audience. In this spirit, the Poznań Oxford Debates were launched in 2012. Since that time, Career Counselling Centre organise the debates, which are popular among the students.

(Article based on the Erasmus+ project Trio2Success outputs)

Learning methods: debate clubs

Debating has a very long history as it roots lie in the Ancient Greece, where it was an important element of everyday life. These debates are now perceived as the beginning of democracy and a possibility to express one’s view in topical political issues (Decaro 2011). London debating societies, which emerged in in the early eighteenth century, continued this ancient tradition. The societies were an important part of the English Enlightenment and democratic open-minded society. They accepted participants from both genders and all kinds of social backgrounds. The discussed topics ranged from politics to social issues. The most famous British Debate Club is Oxford Union Society which operates since 1823 in the city of Oxford. The club has its own building in the city centre. Many politicians have begun their careers by being members the society, but these are only students of the Oxford University who can become the life members. Despite this rule, the society has many notable speakers from around the world (e.g. Albert Einstein, Stephen Hawking, Dalai Lama) (Wikipedia.org). Nowadays, such societies are expanding worldwide, however, the most prominent are still those located in England.

London debate societies inspire modern debate clubs which arise mainly in schools, universities or institutions connected to politics. What is more, recently there is a growing discussion on the role of debate clubs in teaching entrepreneurship (e.g. Harvey-Smith (2011); The future of learning (2013)). Some authors emphasise that debating is more demanding than public speaking, because we are not able to prepare the speech earlier (NLSDU 2011). Thus, participants must develop special skills, which will help to synthesize and express their ideas. As it was emphasised, practising public speaking is also helpful but no essential to start debating, for motivation and regular training are the most important factors of success (Johnson 2011).

Before preparing a debate, it is important to consider the maturity of the students, their skills as well as the time available and size of the class. Remember that debating is quite a spontaneous activity. Usually, there is some time devoted to preparation, but it is very limited. Speakers are required to think fast and consider a wide range of ideas.

There are various forms of making debates, Wikipedia enumerates 19 ways of competitive debating1 which usually differ in some formal and cultural elements (e.g. number of participants, arguing style, philosophical foundations). However, there are some things that are common for all of them. Teacher’s Guide to Introduce Debate (2011) indicate that these elements are:

- a resolution of policy or value that provides the basic substance of the discussion. The terms of this resolution will be defined by the first speaker of the debate;

- there are two teams representing those in favour of the resolution and those against it;

- the affirmative team always carries the burden of proving its point;

- the debate closes with final rebuttals on both sides which summaries their respective positions.

Whatever the debate type, each has its own rules that speakers must follow. In all cases, probably the most important element of the debate is the topic (Quinn 2005). The topic is the discussed subject, which is usually a declarative sentence. Hunsinger, Price and Wood (1967) state that this sentence can take three forms, i.e. a question of policy, of fact or of belief. However, a better topic would be of policy rather than belief or fact, as it gives a perfect room for discussion and arguments: the topic based on facts leaves a little room for discussion, while the topic based on beliefs provides too much of it. Exemplary popular statements which can be used for debating are The death penalty is appropriate; Cell phones should be banned in schools; School uniforms help to improve the learning environment2. The very important issue which is connected to topics of debates is the definition. The affirmative team presents the definition of the topic, which is a concise statement explaining how the topic is understood. The definition provides the initial point of a discussion and is necessary as not all words or phrases can be understood clearly. For instance, in the topic Cell phones should be banned in schools we must define what kind of schools it concerns. All types of schools or any school in particular? What does ban cellphones exactly mean is yet another issue – overall ban or the ban during lessons, etc.

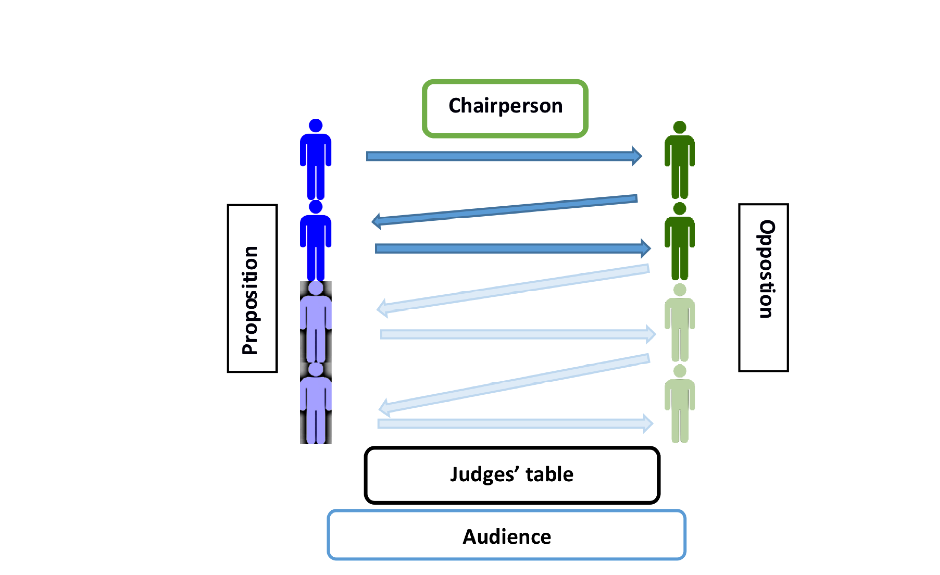

Flynn (2011) specifies that although there are many types of debates in Europe and United States, the British style debates are the most popular. In the British style debates, we have two teams. One team is the affirmative team, which tries to argue that the topic is true. The second team is a negative team, which does not agree with the topic. These teams are often called proposition or government and opposition team (Quinn 2005). Each party consists of two to four speakers who declaim alternately. The general schema of the debate is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. British parliamentary style debate

The hall where the debate is organized is divided into two sections. It is modelled on the British parliament, where parties take places in front of each other. The proposition team takes place on the right of the chairperson. The opposition team takes place on the left of the chairperson. There should be a place for Judges and audience on the other side of the hall as well.

Usually, the debate is controlled by the chairperson, also known as the Speaker of the House. The role of the chairperson is to introduce the teams as well as adjudicators, to present the rules of the debate and to call each speaker in a given turn. The Speaker of the House should also stimulate participation of the audience, control comments and summarize the debate (Gibb and Price 2014). The debate is divided into the number of speeches which are equal to the number of participants. Each speaker has a different role, and the order of presentations is determined by the rules of the debate. Each speech should start with Mr./Madam Chairperson, ladies and gentlemen or Mr./Madam Speaker, ladies, and gentlemen. The first affirmative speaker, called Opening Government (Proposition), has the privilege to define the topic and explain the course of action.

Arguing is a key element of debating. Arguments are usually facts which support one side of the topic. There are basically two types of arguments: substantive and rebuttal. The former includes arguments which are in favour of a given topic, while the purpose of the latter is to attack the arguments of another team by presenting the opposing statement. The simple distinction can be made between these two types of arguments. The substantive arguments prove why the given team is right, while rebuttal show why the opponents are wrong. It cannot be stated that one of these types is stronger and should be preferred (Quinn 2005). Hunsinger et al. (1967) add refutation, which is a negation of argument by giving the counterargument, to the list of types of arguments. In that sense, refutation is close to rebuttal with the main difference lies in the argument (another argument vs opposite argument). Literarydevices.net highlights three ways of making refutation, i.e. refutation through evidence, refutation through logic and refutation through exposing discrepancies.

Refutation through evidence must be based on arguments which are supported by facts (i.e. data, research or theory). Therefore, the speaker can refute the argument of another team by negation or provision of a more accurate evidence. Refutation through logic is very difficult. It is based on deconstruction of the opposing argument and presenting it in such a way so as to point the discrepancies emerging in the argument. The last way of making refutation (through exposing discrepancies) involves indicating that some elements of speech are not coherent or are irrelevant for the topic. The following examples of refutation speech are cited below:

- There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

Martin Luther King, Jr

- We can put a road in and increase everyone’s taxes by 50 cents per day for the privilege of using this new road or we can leave it to consider the future in hopes of the economy getting better. In the meantime, the cost of maintenance of a dirt road and the wear and tear and maintenance on our cars will continue to increase. The future cost of the road will also increase. So, for less than a weekly trip to the car wash, we can have a clean dry road and reduce the dust in our homes along our new road or continue to replace springs and shocks and clean the dust and think about it tomorrow when it will cost more.

www.speechmastery.com

Every debate must finish with a result, which must be carefully worked out by the team of judges. The number of judges typically oscillate between 3 in the preliminary round and even 9 adjudicators in the final round (Harvey-Smith 2011). The author provides some general guidelines which an adjudicator should keep in mind:

- assess from the viewpoint of the average reasonable person;

- analyse the matter presented and its persuasiveness, while disregarding any specialist knowledge the teams may have on the issue of the debate;

- do not allow bias to influence their assessment;

- do not discriminate against debaters on the basis of religion, sex, race, color, nationality, sexual preference, age, social status or disability.

Judges must be objective, i.e. suspend their private opinion and focus on the provided arguments.

Usually, the adjudicator considers three categories to assess the debates. They are:

- manners, i.e. the way that particular speech is presented; how interesting, sincere or humorous the speaker is;

- matter, i.e. the quality and strength of the arguments; the way in which the arguments were presented;

- method, i.e. the structure of the speech.

There are also another categories provided by the World Schools Debating Championship: style, content and strategy. However, in that case, style equates to manners, content to matter and strategy to method. These categories are usually of unequal importance in the assessment process. The strongest are matter and manner while the method is less significant (Johnson 2009).

Entrepreneurship Skills (2015) emphasise that some entrepreneurship skills can be taught and learned, however, the most effective approach is to focus on real problems. The debates are very helpful in developing oral skills. Quinn (2009) points to the fact that debating can develop such skills as comprehensible speech, persuasive communication as well as giving one’s speech a proper structure.

Obviously, debates are not individual speeches. All speakers need to connect their performances to other presentations and not contradict the speeches delivered by the members of their own team (Debating 2008). Thus, only good cooperation can help the team become successful. The ability to work with others is essential in this type of activity. It is important especially when the members of the same team do not know each other well. In his handbook, Quinn (2009) focuses on the role of tactics in winning the debate as well. Another issue is developing social ease among the participants. It has to be kept in mind that debating is a highly stressful situation. The participants are obliged to develop their speeches in a short time standing in front of adjudicators, opposite team and audience. Social ease is essential for successful speaking to the large audience. Practising speaking and arguing can significantly improve this skill (Johnson 2009; Harvey-Smith 2011).

In conclusion, there is a straight link between the ability to co-operate with others, social ease, comprehensibility and debating. Participation in the debates can be a great opportunity to develop this set of skills. The rule is simple: the more practice, the higher level of speaking-related skills is achieved.

Poznań Oxford Debates

Oxford-style debates have been popularised in Poland by Zbigniew A. Pełczyński, a long-time professor at Oxford, who founded the NGO School for Leaders in 1994. Due to the influence of scholarship programs launched by this organisation, Oxford-style debates have spread quickly among politicians and activists, not to mention teachers and students of both schools and universities. The rules have been slightly modified from the debates at the Oxford Union, yet the most important elements have been preserved (www.cdzdm.pl).

The first national debates tournament in Poland was organized in 2008 by the Foundation for Youth Entrepreneurship. In the next edition in 2009, 79502 pupils from 904 schools and 1312 teachers participated in the tournament. One of the stages was organized in Poznań on 28th October 2009. The CEO of the Career Counselling Centre for Youth – Mrs. Bogna Fraszczak was one of the observers. This debates as well as debates organized by the Polish-American Freedom Foundation inspired Mrs. Fraszczak to start the separate debate event in Poznań.

Since 2012, the debates have been cyclically organized by the Career Counselling Centre for Youth in Poznań. The event usually takes place in Autumn or Spring. During the first stage all upper-secondary schools in Poznań are invited to enter the tournament. The application is made by the teacher representing his or her team. In 2014 eight teams entered the tournament. In 2015 there were 13 teams that wanted to participate in the competition.

After the application period is over, the preliminary stage begins. In that stage, each team participates in special training provided by the employees of the Centre. The training covers such areas as self-presentation, debate rules and argumentation. One training session lasts 4-6 hours. Two to three teams takes part in one training session.

The debate is organized by the main Speaker – chairperson, who does not take part in the discussion. The main speaker is impartial. He or she is supported by the secretary. The main duty of the secretary is to watch the time, fill in the documents and signalize the end of the debate with a bell or ring. Prior to the debate participants take places according to the figure 1, i.e. the proposition sits on the right of the Chairperson. The opposition sits on the left of the chairperson. Judges and audience sit in the back of the hall. The first seat of the proposition and oppositions are held by the first speakers of each team. Each participant must start the speech with the words Sir or Madam directed to the chairperson. Participants have to address each other with the words Sir or Madam. There are four speakers on each side of the debate. It is important to note, that the panelists typically do not choose their stance – the roles of the “proposition” and the “opposition” are assigned in a draw. The speakers who defeat and oppose the topic speaks alternately. The first to speak is the representative of the proposition who should define the topic. The other speeches should revolve around the topic defined by the first speaker. The last speaker sums up the arguments of each side and represents the opposition. Speakers have to obey the time, because if they exceed the time, the chairman interrupts their speeches. The audience can ask questions or provide information by standing up and saying question or information. Questions can be asked at the end of first and at the beginning of the last minute of the debate. The speaker can accept or refuse interjections from the audience. Interjection should include up to three sentences. The teams can report neither questions nor information. The photo of the 2015 debates is presented below. As can be seen, the general arrangement of the hall is similar to this presented in Figure 1.

Picture 1. The Career Counselling Centre for Youth final debate 2015

The tasks for speakers from proposition and opposition are presented in Table 1. Notice that each member of the given team must be in close touch with the previous speaker and pay the highest attention to the speech of the opposite team as well.

Table 1. The speakers’ roles in the Poznań Oxford Debates

| Proposition | Opposition |

| The first speaker (5 minutes)

· Provides definition and criteria · Sets out the arguments |

The first speaker (5 minutes)

· Refers to the definition and criteria · Sets out contrary arguments to the statements presented by the first speaker of the proposition · Presents his/her own arguments |

| The second speaker (4 minutes)

· Strengthens the proposition’s arguments · Presents contrary arguments to the statement presented by opposition’s first speaker |

The second speaker (4 minutes)

· Contests the proposition’s arguments · Strengthen the opposition’s arguments |

| The third speaker (4 minutes)

· Strengthens the proposition’s arguments · Presents contrary arguments to the statement presented by opposition’s second speaker |

The third speaker (4 minutes)

· Contests the proposition’s arguments · Strengthen the opposition’s arguments |

| The fourth speaker (4 minutes)

· Sums up the proposition’s arguments · Sums up the contrary arguments to speeches delivered by the opposition |

The fourth speaker (4 minutes)

· Sums up the opposition’s arguments · Sums up the contrary arguments to the speeches delivered by the proposition |

There are four judges in each round of the tournament. One of them is the leader, who presents the verdict to the teams and makes a short summary. In this summary, the leader of the judges tries to elaborate on strong and weak points of each speaker. Moreover, the judges choose the best speaker – the participant who was the most successful in fulfilling tasks assigned to his or her role. The best speaker can represent the team which lost the match as well. Judges in the Poznań Oxford Debates are asked to assess the following issues:

- organization of the speech – structure (introduction, end);

- arguments – quality and content;

- proofs – what proofs (data, research, publications, statistics, sources);

- presentation – quality of speech (fluency, vocabulary, body language, gestures).

Exemplary debate topics discussed during Poznań Oxford Debates organized by the Career Counselling Centre for Youth in April 2015 included:

- Following well-trodden path is better than appoint new trail (elimination round).

- It is better to live in the centre of a large city than in the neighbourhood area (third place debate).

- Higher salary is better than an interesting job (final debate).

Members of the audience can be involved in the discussion in a variety of ways: questioning the panelists, giving them additional information, taking the floor after the main debate is finished as well as giving short speeches supporting either the proposition or the opposition. In Poland, the rules are very relaxed when it comes to the mode in which the winning side is chosen: depending on the circumstances, the organisers may resort to an audience vote or decide to appoint a panel of judges, who grade the quality of the panelists’ arguments, presentation as well as the use of evidence. The latter model is often considered to be more reliable in case of school competitions and large tournaments.

Benefits and conclusions

Debating can be a very enlightening experience for each person engaged in the process. The method undoubtedly develops the entrepreneurial skills among the participant. It is especially useful in extending social ease, comprehensibility and ability to work with others. The main benefits were described in relation with the three groups: youth workers, counsellors and teachers.

The benefits for young workers:

- developing entrepreneurial skills needed in business practice;

- developing negotiation and persuading skills – also very useful in everyday business practice;

- learning about the discussed topics – the topics are often connected to politics, economy, finance, which can broaden the young workers’ horizons as well;

- the ability to find the facts, arguments or data.

The benefits for counsellors:

- cognition of students’ predispositions in a real-life situation;

- expanding personal network as the tournament gathers teachers, counsellors and students from many schools and other institutions;

- extending one’s own knowledge.

The benefits for teachers:

- learning new, innovative teaching method;

- improving the quality of relationships with your students;

- extending one’s own knowledge as well as the students’ knowledge.

Career Counselling Centre for Youth has been organizing the Oxford Debate Tournament since 2012. It needs a lot of effort to make it run smoothly as many employees have to be involved in the organisation process. The planning of the debate starts usually many months earlier – if the tournament starts in October, some initial works must be done during the summer holidays (June – August). Primarily, training programs for participants must be prepared, some collaboration with schools have to be established, etc.

Some external reading is recommended in order to develop some topics, which may be interesting for the readers. For general information you can visit the website of Career Counselling Centre for Youth (see Events), which is available in English as well. You will find some photos from the debates, list of teams and dates there. Much more detailed information can be learned from the excellent, universal handbook by Quinn (2005). The handbook is divided into sections for the beginners, intermediate and advanced readers, thus it is easier to start with your level of knowledge. The teachers may be interested in the well-developed work by Harvey-Smith (2011), which also presents the historical, social and organizational background of debates.

References

Ad rem. Konkurs dla uczniów szkół ponadgimnazjalnych, Ministerstwo Skarbu Państwa, Fundacja Młodzieżowej Przedsiębiorczości, 2009.

Debating. A Brief Introduction for Beginners. Debating SA Incorporated 2008.

DeCaro, P. (2011). Origins of Public Speaking. The Public Speaking Project. http://www.publicspeakingproject.org/.

Entrepreneurship Skills: Literature and Policy Review. BIS RESEARCH PAPER NO. 236, Hull University. Business School 2015.

Gibb, A. Price, A. (2014). A Compendium of Pedagogies for Teaching Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship in Education.

Harvey-Smith, N. (2011). The Practical Guide to Debating. Worlds Style/ British Parliamentary Style. International Debate Education Association New York, London & Amsterdam.

Hunsinger, P. Price, A. Wodd, R. (1967). Debate Handbook, University of Denver, Toastmasters International, California.

Pankowsk, R. Pawlicki, A. Pełczyński, Z. Radwan-Rohrenschef, P. (2012). W teatrze debaty oksfordzkiej Przewodnik debatancki Szkoły Liderów. Stowarzyszenie Szkoła Liderów: Warszawa.

Philips J, Hooke J (1998). The Sport of Debating: Winning Skills and Strategies. UNSW Press, Sydney

Quinn, S. (2005). Debating. Brisbane, Australia.

Quinn, S. (2009). Debating in the World Schools Style: a Guide. International Debate Education Association. New York, Amsterdam, Brussels.

Teacher’s Guide to Introducing Debate in the Classroom. Speech and Debate Union, New Zealand 2011.

Rooney says:

It is apparent that the author is a statistics geek.

I enjoy how he writes and writes facts.

Tobias says:

I’ve been hunting for a post similar to this for quite a long moment.

Cecile Wanamaker says:

The more I read, the more the greater your substance is.